Featured Photographer: Cindy Konits - “This Room Will Survive Me”

“Mia Vida”

There is a particular hour of the afternoon when a room stops behaving like background and starts behaving like an invitation. Light slips in at a slant, hitting the wall just above the baseboard, crawling across the floor, grazing the edge of a doorway. If you cross the threshold into the room, you are no longer looking at the light; you embody it, and your gaze turns inward. Cindy Konits has spent the last several years inside that hour, turning light and emulsion into a field laboratory where architecture, memory, and metaphysics coalesce—not as abstractions, but as daily, repeatable phenomena traced in time and material. Her monograph, This Room Will Survive Me, forthcoming from Schilt Publishing and debuting at the 40th Anniversary FotoFest Biennial in 2026, records this sustained investigation through a sequence of sixty instant photographs, edited from hundreds and bound using Japanese binding. Designed as an art object, the book asks to be handled and viewed at roughly the same tempo in which the work was made: slowly, attentively, one measured interval of time at a time.

“It’s a discovery about the existential experience that architecture is. Architecture is not the buildings out there; it’s the mediation between my mind and the world.”

“The Window”

“No”

This Room Will Survive Me began not as a book, but as an inquiry into how interior experience takes form in space. Psychoanalysis has historically located inner life within the analytic room, treating it as a structured environment for reflection, presence, and the unfolding of thought over time. Konits extends this cultural model beyond the analytic setting, using architecture itself as a site where inner experience becomes perceptible through movement, duration, and attention.

In 2019, in the back of her studio, she encountered the tool that made this exploration possible: an obsolete Fuji Professional instant camera. Its bellows and tiny f/64 aperture, paired with expired Fuji FP-100C film and an ND filter, required long, uncertain exposures—fifteen to thirty seconds, sometimes longer. These technical constraints demanded stillness and heightened awareness, turning the act of photographing into a sustained engagement with space and time.

Equipped with the last batches of peel-apart color stock ever produced—discontinued by Fujifilm in 2016—the camera invited chance and material intervention. Wet residue left on the negative could be pressed back onto the print, producing a second, ghosted impression. The resulting images became composites of emulsion, error, and touch, reinforcing the sense that interior experience is never singular or fixed, but layered and evolving.

“The End”

“It’s simple. You ask, ‘How am I feeling in this space?’ Be more aware of how different rooms make you feel, behave, and relate to others differently.”

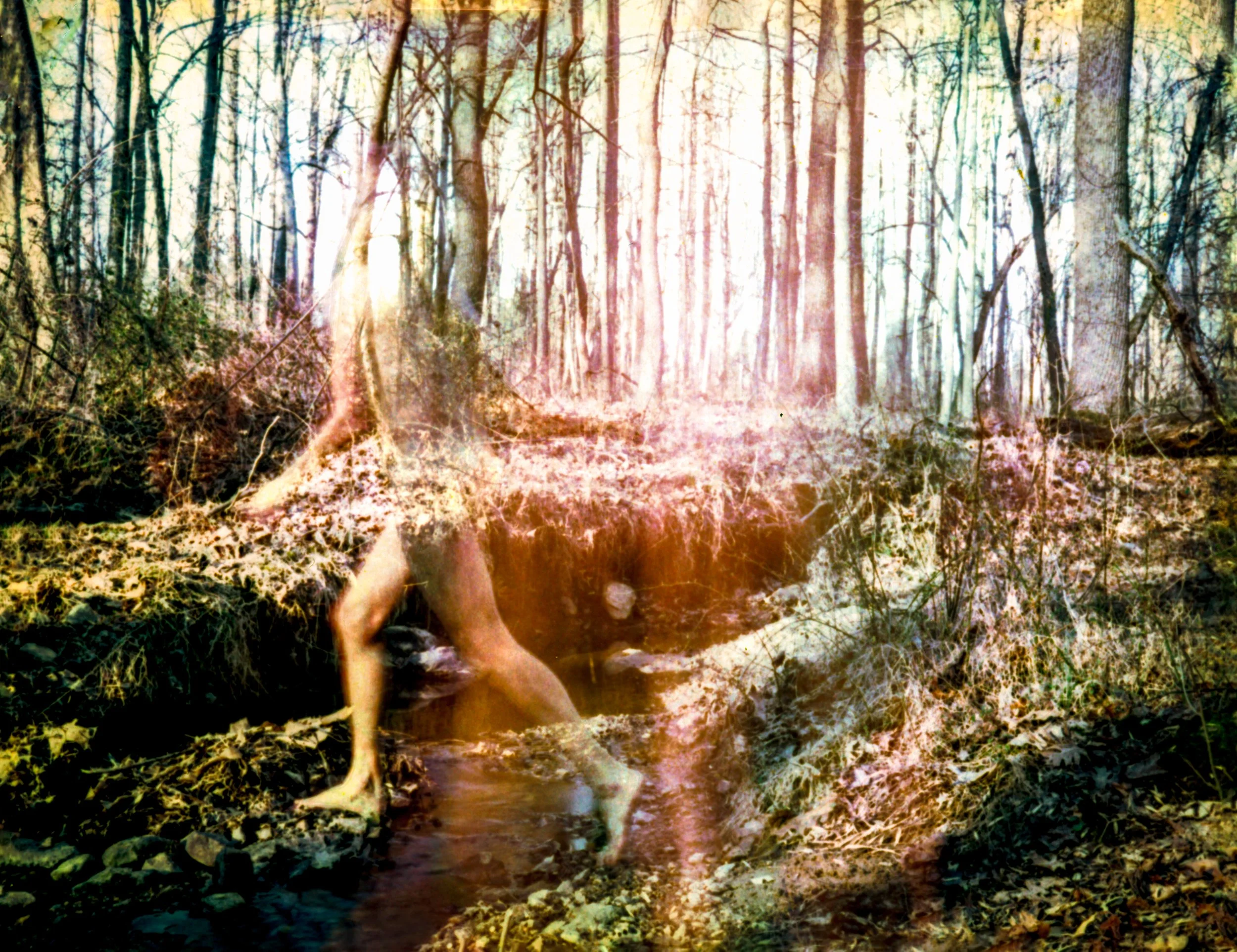

The resulting self-portraits feel less like scenes observed and more like amalgams of places and selves existing on the same plane. In The Window, a bedroom’s toile wallpaper—patterned with pastoral churches, trees, and strolling figures—bleeds into a forest of pines. Konits’s translucent body becomes both patterned fabric and forest air, her white dress a hinge between inside and outside. Window mullions, tree trunks, and printed branches stack upon one another until it is unclear whether we are looking out from a room into the woods, or back into the room from somewhere between the trees.

In No, a bathroom interior is overtaken by streaks of color and ghosted lines, the emulsion lifting and sliding so that the figure appears to move both into and out of the frame at once—part reflection, part residue, part trace. Across the series, architecture, landscape, and photographic chemistry collapse into visualizations of interiority: the space where creative imagining, feeling, and memory are formed through the continuous exchange between inside and outside.

“Blinded”

Beneath Konits’s spectral imagery of bodies dissolving into wallpaper, stretching across doorways, or curled into chairs beside sun-washed windows lies a persistent question: what exactly is this thing we call interiority, and where does it live? We often imagine the self as a sealed interior, a private chamber behind the eyes. Yet consciousness unfolds in rooms—in bedrooms and hallways, kitchens and stairwells, in the narrow zones between window and wall where time both reveals and withholds. The mind does not hover above these spaces; it is shaped within them.

This understanding draws on two complementary intellectual traditions. Architectural theorist Juhani Pallasmaa describes architecture as a mediation between the world and the mind, emphasizing the role of embodied perception in shaping experience. Psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, writing from a developmental perspective, understood interiority as a lived space of time formed between inner experience and the external world—a space where presence, creativity, and a sense of reality emerge. Konits treats these ideas not as citations, but as working conditions.

If experience is already structured by space and time, and if buildings domesticate that structure into daily routines, then the rooms we inhabit—especially the earliest ones—function as quiet instruments of formation. They teach us, often without our awareness, what it means to be alone, to be seen, and to belong. Konits’s photographs operate within this premise, repeatedly asking whether what we call “inside” might actually be an ongoing negotiation between walls, thresholds, and the body moving among them.

“Sinew”

“My goal in this work, if not in all of my work, is to express the importance of self-reflection—the importance of knowing yourself. In this case, to walk into a room and notice what it makes you feel.”

What makes This Room Will Survive Me accessible, even as it engages abstract questions, is its commitment to the ordinary. These are not iconic buildings or grand interiors, but rooms most people recognize: modest bedrooms, narrow hallways, doors left ajar, a sliver of outside visible through a window. The work does not ask viewers to decode biography; it asks them to recognize how thoroughly their own lives have been shaped by the places they have inhabited—and how those places continue to inhabit them.

The title initially reads as a concession to mortality. Over time, it reveals itself as a description of reciprocity: we build rooms, rooms build us, and the photograph holds that exchange long enough for someone else to step inside and feel the echo.

What ultimately lingers is not only the distinctiveness of the images or the rarity of the materials, but the way the work repositions where we look for ourselves. Konits does not offer resolution, but conditions: a body, a room, a moment in time, a fragile piece of film. The rooms she moves through will outlast her, just as the rooms that formed us will outlast us. The photographs slip into that interval, holding open the brief moment when we can still feel the exchange moving both ways—and recognize where it is already at work in our own rooms.

GALLERY

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Cindy Konits (b. 1954) is an American artist based in Baltimore Maryland and NYC. Her practice is lens based, encompassing a wide range of media to explore family history, memory, and identity. Her first experiments with photography became the solo museum exhibitions “The Best Woman for the Job” and “Now I See Kiev in My Dreams” with NEA and NEH grants to the exhibiting institutions respectively. Konits’ documentary short “The Way I See It” about her cousin who was Albert Einstein’s ophthalmologist, screened in 19 film festivals worldwide and was nominated Best Documentary Short. Her interactive work on CD-ROM “The I for Pleasure”, was curated for exhibition at The Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, and censored days before the show opening. In response to this and coincidental censorship at another prominent Baltimore art institution, Konits created the video “The Veil of Intent”, screened at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Konits won first prize in The Photo Review Competition 2021, and second prize in The Photo Review in 2022. She has won numerous Julia Cameron and Pollux awards, Honorable Mention at ‘Fresh’, Klompching Gallery, and exhibited in The Exhibition Lab, Foley Gallery, NYC. Her work appeared in “In the In-Between”, “Enimazine” and “F-Stop” online and in Shots Magazine, Photonostrum Magazine, and Creative Quarterly Journal of Art and Design.

She won a full merit scholarship to the Maryland Institute College of Art, then became adjunct assistant professor for photography and video art at Stevenson University, Baltimore. She designed the Digital Photography curriculum there at Stevenson University.

Konits researched and designed a cybersecurity awareness installation “Digital Intimacy” with the White House Office of Management and Budget IT Manager and with support of the DARPA Cybersecurity Program Manager. Konits also developed an online realtime collaborative family video editing project “Bits of Us” involving a new technology for the web. Fundraising for these projects remains in hiatus.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Behlen is an instant film addict and the founder and publisher of Analog Forever Magazine. Behlen is an obsessive community organizer in the film photography world, including previously launching the independent publishing projects PRYME Magazine and PRYME Editions, two enterprises dedicated to the art of instant film. Through these endeavors, he has featured and published 250+ artists from around the globe via his print and online publications.

He has self-published two Polaroid photobooks -“Searching for Stillness, Vol. 1” and “I Was a Pioneer,” literally a boxed set of his instant film work. His latest book, Searching for Stillness Vol II was published in 2020 by Static Age.

Behlen’s Polaroid photography can be found in various publications including Diffusion Magazine, Fraction Magazine, Seities Magazine, and Polaroid Now (Chronicle Books, 2021). He loves the magic sensuality of instant film: its saturated, surreal colors; the unpredictability of the medium; its addictive qualities as you watch it develop. He spends his time shooting instant film and backpacking in the California wilderness, usually a combination of the two. Connect with Michael Behlen on his Website and on Instagram!

In This Room Will Survive Me, Cindy Konits uses afternoon light, architecture, and expired instant film to examine interiority as something formed in the rooms we inhabit. Through long, uncertain exposures and chance-driven chemistry, her images merge body, space, and memory into scenes that feel lived rather than observed. The work leaves a quiet proposition: our inner lives are shaped in thresholds, light, and time, and rooms continue to shape us long after we’re gone.