Interview: Terri Warpinski - Exploring Landscape, Memory, and Borders Through Photography

Terri Warpinski is a visual artist and photographer whose work navigates the intersections of landscape, memory, and human presence. With a background in fine art and an academic career as a professor of art at the University of Oregon, Warpinski has spent decades investigating how personal and political narratives are embedded in physical spaces. Her photographic practice extends beyond traditional landscape photography, often incorporating historical and mixed-media elements to engage with themes of resilience, displacement, and environmental change.

Warpinski’s creative process is deeply rooted in fieldwork and immersion. She travels extensively, observing how land carries the weight of history and how natural and human forces continuously reshape it. Her images frequently blur the boundary between documentary and abstraction, using texture, layering, and altered perspectives to evoke a sense of place that is both deeply personal and universally resonant.

One of her most compelling projects, Restless Earth, is a profound meditation on the shifting, unstable nature of landscapes affected by geopolitical and environmental forces. Through this body of work, Warpinski examines regions where borders—both natural and man-made—have been sites of conflict, transition, or erasure. Whether focusing on the rugged terrains of politically fraught territories or the subtle scars left by human intervention, Restless Earth speaks to the impermanence of place and the ongoing tension between nature and civilization.

By juxtaposing images of expansive landscapes with intimate details of their transformation, Warpinski invites viewers to contemplate the fragility of our connection to the land. Her work serves as both a visual archive and an artistic inquiry, encouraging a deeper understanding of how the earth, in its constant state of flux, reflects our own histories and struggles.

Warpinski’s work was included in the Top 50 for Critical Mass in 2024 and we felt it necessary to investigate more about her background, creative process, and the road to making such immersive installations in this equally fascinating interview.

INTERVIEW

Michael Kirchoff: Every visual artist experiences that spark that drives them in the direction of image-making. How did you get your start, and what were your early influences?

Terri Warpinski: There is not a time in my consciousness that I did not have the ‘art spark’. My first memories date back to when I was just about 3 years old, so there it begins. For those first few years of my life I was an only child born to two teachers (ultimately, I would have six siblings). My paternal grandmother was my caretaker during the school year. She had, in her 50’s, begun painting. Her way of keeping me occupied was to set up a table alongside her easel with drawing paper, watercolor paints and crayons and guide me to copy what she was painting. I adored her! My grandparents were the children of Polish immigrants. They were struggling farmers. They lived in the township of Poland where even the priests in the church delivered the homilies in Polish. They spoke little to no English until their own children went to school, ultimately learning the language from them. My grandmother’s favored subjects were largely drawn from illustrated books and her family photographs; sometimes she would set up a still life. My youthful influences in art were very traditional. I eschewed the usual toys for books, sewing kits, and art supplies. I was an avid follower of the Jon Gnagy’s Learn to Draw series on television (your readers will all likely have to do a deep search to find more out about what that was!). As I progressed in age and experience, the art education I was delivered was also very classical – such as having to study anatomy in drawing class, copying Da Vinci drawings to learn about the human figure, with the only approved method of rendering tone and value being accomplished through painstaking cross-hatching with fine pointed drawing tools.

Anyway, it was toward the end of my undergraduate studies (printmaking and fibers were my dual emphases in studio art) I was wandering the stacks in the library looking for inspiration for a project in my Surface Design on Textiles course when I had my ‘ah-ha’ moment upon finding a book on alternative photographic practice that included photo-silkscreen (with illustrations of Robert Rauschenberg’s combine paintings) and some of Betty Hahn’s Van Dyke Brown and mixed media Lone Ranger and Tonto pieces. My mind was blown. Truthfully, up until that point I had completely dismissed the camera as an instrument for making art. I ran (literally) to meet with the photography professor, Jerry Dell, to see what it would take for me to learn those techniques. I enrolled in Intro to Photo, borrowed a Pentax K-1000, bought a copy of Bea Nettles Alternative Processes Cookbook, got to know the University’s Chem Stores, stocked up on raw chemicals and amber jars, and borrowed a gram scale. The art faculty allowed me to clear out a janitor’s closet on the floor that housed all the art studios. I bought a UV bulb, a roll of black ™Visqueen. And away I went.

MK: What is at the core of your work? Is there a theme that runs through everything you create?

TW: My short answer is that most of my work, dating back to 1980, or thereabouts, sits at the intersection of histories – natural, cultural and personal. Others may quickly cast my work into the mold of landscape photography. When I look at a place (any place really) I don’t see it as a “landscape” but rather as an environment - be it ‘untouched’ or vastly altered by human hands. I see and understand the world in which we live as a layered narrative - a palimpsest that, upon careful attention to detail, reveals its story.

MK: I was especially smitten with your installation and assemblage work upon learning more about it after making the Top 50 in Critical Mass last year. Can you tell me more about the intentions for Restless Earth?

TW: This is not going to be a short answer! Restless Earth had its beginning during the pandemic. I was in the midst of a long-term project that was based in Berlin. That forced a ‘pause’ – or maybe… even a ‘quit’ – as I am I uncertain if I will ever get back to that project. So, in the absence of that travel I began focusing on my own locale as a way for me to be out in the world, and way to keep myself creatively engaged. I had recently retired from a 30+ year teaching career in Oregon, and came back to my home ground, Wisconsin - a place I thought I knew well. Concurrently, I was invited to create work for an exhibition at the local university inspired by the collections of their natural history museum. These two events, the pandemic and the invitation to work in response to a natural history collection largely gathered from local flora and fauna, conspired to form the early seeds for Restless Earth. It drew me to engage with some of the local land trust properties, to spend time getting to know their histories, and to imagine their futures.

MK: On your website, Restless Earth is broken up into sub-categories like chapters in a book. Is there reason for this, and does this help you to tailor an exhibition to a specific space?

TW: Thank you for this question. First, I appreciate that you looked at my website – these days one wonders if anyone does such anymore! Secondly, that you noted that there are subsets to the work. This work, as it continues, does take on/explore/examine issues related to the environment from an array of vantage points ranging from despair to delight; from manifesto to lament.

Are they as crisp as chapters in a book? Not yet. When I think about such things, Richard Misrach’s Desert Cantos readily comes to mind. I largely proceed on intuition and instinct when I am first aware that my work is pulling me in a particular direction. I don’t stop to study the situation and devise a methodology for moving forward. Honestly, at first, I simply indulge my creative impulse and curiosity in whatever way is most expedient. And in doing so, try to determine if there is more there - is there a deeper dive? And, if the answer is yes (or even maybe), then begin the more difficult endeavor to figure out how the content informs the working methods, material choices and final form. As you noted, Restless Earth engages more than one working method, more than one material strategy, and multiple forms presentation. In part, that is due to the complexity of the content given the many strands to the narrative I wish to weave together, along with my best attempts at creating art that in and of itself is not further accelerating the very problem it is addressing, and lastly, but importantly, one that relates to its audience in a manner that is as fragile and vulnerable as the viewers themselves.

Certainly, the variations in form and scale do allow for tailoring the work for many different types of exhibitions and exhibition spaces. I can’t claim credit for doing so consciously. It was only in this last year, with the Carol Crow Fellowship Award from the Houston Center for Photography, that I was able to see more than 3-4 pieces installed together. Since then, more such occasions have occurred and with each of them, I am gaining deeper insight into my work and how it engages/interacts within itself in a larger dialogue.

MK: In your experience, how does your relationship with a landscape change when you photograph it over an extended period of time? Has this resulted in an evolving narrative for any of your subjects?

TW: I think it is lot like looking at your own face in the mirror every day – it is easy to not really see it as time passes. But I have been afflicted with multiple occurrences of skin cancer - mostly on my face - and so looking closely, examining every little change is imperative. The sites I visit the most carry that kind of scrutiny. That level of intimacy means that I both mourn and revel in the changes I see. A tree falls over in a windstorm. It was a favorite character in a scene. It is a tragic loss. But a new character is revealed. The now upright root reveals a cavern in the ground below that various critters inhabit, a crop of flora spring to life on top of it all. Seasons change. The wind blows, carrying soil and decaying organic matter to rest up against the upright roots. The topography of the woodland floor begins to change – I am convinced I see the beginnings of a hill forming. And that is how the narrative might evolve.

MK: Is there anything about your work that you feel people miss or are misinformed about?

TW: I don’t know if I have any way to get a handle on that. I do know that some who see my work find more than I consciously knew to be there and through them I learn…

MK: What does a typical creative day consist of for you? Do you consider yourself a workaholic, or do you keep a schedule of time for family, socializing, vacation, etc?

TW: You probably should ask someone else, such as my husband, this question! In my mind, every day is a creative day – some days are very active while others might appear dormant. I am rarely not ‘working’ at some level, meaning it is very difficult for me get my brain to quiet down. An example would be waking up in the middle of the night with an answer – or a strategy – for dealing with a challenge I am facing in my work. My studio practice, besides requiring time and opportunity out in the natural world to be making photographs, also includes research. I spend significant time reading – some material that is broadly on topic, such as that of our most knowledgeable authorities writing on the climate crisis. Other research could be trained on specific locations and might include digging into archeological studies or tracing the history of land contracts and property transfers since settlement; or going through historical archives looking for a photographic record over time. And then there is the time exploring materials, testing samples, editing images and experimentation with scale and presentation.

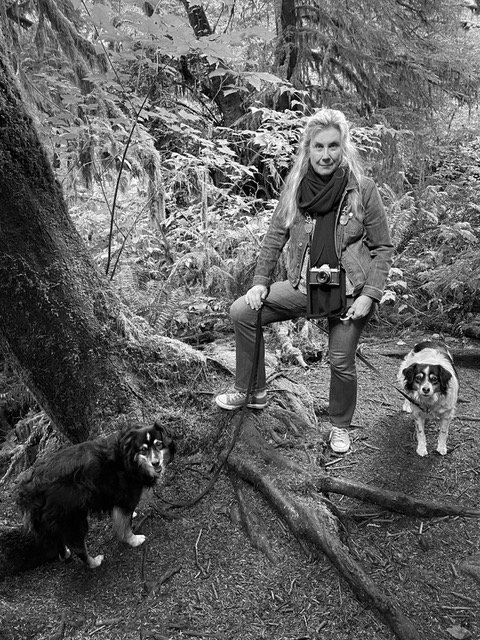

Besides my studio practice, I spend time (daily) along with my husband overseeing/managing/running a non-commercial gallery and event space in our community. It is an old, rehabilitated storefront which houses our shared studio and storage/archive behind it. We are very active in our community, especially around matters of advocacy for the arts and culture sector. Our recreation/vacation time is also often centered around art and art making as well. We typically travel to see major exhibitions and consume as much culture as we can absorb with visits to NYC twice a year. For my own production, my preferred seasons to photograph in the woodlands and forests are when there is no canopy, which we satisfy by doing frequent day trips to hike and shoot during the fall and early spring. In the winter we resort to snowshoes and cross-country skis. (Our two dogs, Luna and Mojo, enjoy racing about in any conditions).

My husband’s work is documentary -- little suits his needs/purposes more fully than a road trip, especially off the interstates on local highways and into the small towns. We often will drive to deliver work for exhibitions, or to attend conferences, to satisfy that.

MK: Do you collaborate with like-minded individuals on projects, or do you find it more productive to handle everything yourself? Are there any collaborations in the past that have been particularly beneficial?

TW: I love collaboration. I find it expands, complicates and deepens my understanding of my work. My experience with collaboration is varied in form - I have worked with writers, both prose and poetry; with book artists, designers and letterpress printers; with other artists in other media (painting and fibers); and with artists in my own medium. As a partner in newARTSpace with my husband, and serving as curator, I see almost every exhibition we put together as a collaboration. But for this question I want to focus on my involvement with a collective – The Women’s Environmental Photography Collective – as the most beneficial of collaborations I have been a part of when it comes to informing and influencing my creative practice. Here is it the medium and our shared commitment to content that fosters a rich and potent connection. Our collaborations are various, we have joined together on conference and symposia panels, and in multiple exhibitions. We dream of creating truly collaborative artwork, but have not, yet accomplished that. The most profound aspect of this collaboration is intellectual. We typically convene monthly. Our agenda varies, but most commonly is built around a workshare in which one or two of us presents a work-in-progress for feedback. We are geographically dispersed – from Connecticut to Arizona, New York to New Mexico, another in Nebraska and me in Wisconsin. Our meetings are virtual. They began back in 2020, coinciding with the onset of the pandemic - which was not what instigated the group, but certainly accelerated our desire to connect.

MK: How do you know if you’re ever really done with a specific body of work? Do you ever go back to revisit images or collections to improve upon what you felt was previously finished?

TW: I really see the continuum in my work, the threads that bind and cohere rather than the stops and starts. Honestly, I have to say it is usually only through the rear-view mirror that I understand that I have moved on into a new direction – you know, rounded the bend so far that you no longer can directly see where you came from? In only a few instances in my mature creative life – meaning over the last 50 years - that I have abruptly moved from one path of inquiry to another, and that usually was due to some significant rupture. Some examples of that might be a major shift in geography – moving from Florida to Oregon; or the death of my spouse; or taking up new tools (digital) and new methods (working in color) for the purposes of teaching in my curriculum; or the pandemic.

MK: Over the years, the tools we use to make photographs have changed in dramatic ways, not to mention the vehicles we use to promote the final works we make. How do you keep up with these changes, and do you see there being any further significant change as lens-based media continues to progress?

TW: My head hurts to even think about this one! Keeping up with the pace of technological change could be a full-time occupation. I can’t do it all, or rather, maybe I no longer feel like I need to do all. As an educator, it was part of my job, but since I retired (9 years ago) I choose to focus on what matters most for work I feel the urgent need to make. Sometimes my hand is forced – a tool becomes obsolete or impossible to update, and sometimes it is because I have a notion of somewhere I want to go with the work, and, to get there, I must get over a technical hurdle. Additionally, we are all talking about AI now and its effects on our world-at-large, and our medium-in-particular. I do not imagine it becoming part of my creative toolbox, but then, I hope I am wise enough now to not rule it out.

MK: Your use of texture and form is striking, particularly in how you capture the interplay between organic elements and the environment. What role does the tactile nature of your subject matter play in the way you compose your shots?

TW: That is a provocative question and by that, I mean, I haven’t directly thought about it - my composition in camera – as being responsive to texture or intending to elicit tactility. My predilection to working in monochrome certainly is owing to that desire. As is my choice in materials and presentation. In the viewfinder I am most keenly attentive to the major dynamic movement within the frame – how the viewer would initially enter the frame/image, and, then progress through it. Since most of the works in Restless Earth use more than one frame of exposure to create the final image, I am always thinking about how elements connect - one to another – and what I might want to have the opportunity to do with those elements when I am back in my studio. So, in the field, I am really obsessed with collecting the building blocks.

MK: Anyone working in an artistic field has matured and grown over time. Is there anything you’ve discovered lately that you’d like people to know about you or your creative process?

TW: It’s a bit cliché but, never say never. I never imagined that I would choose to live in the Midwest again after spending 3 decades in the Pacific Northwest. I never thought I would marry again, but 20 years later…. And now, here I am. And that holds true, never saying never - to making work that matters and that is valued. It’s never too late.

MK: Finally, how do you see your work evolving next? Is there anything on the horizon that we may see from you in the near future?

TW: I’ll tell you when I get there! But seriously, if I will allow myself the folly of predicting the future, my current creative impulses are pulling me further in the direction of installation, increasing scale and the use of space. In the past six months, two exhibitions arose where each allocated an entire gallery to my work. In each instance I saw synergies and new opportunities occur by having pieces of work in proximity for first time. With that observation, I am compelled to think more about the entirety of the experience and the opportunities to further relationships between what are now individual works and between the work and the viewer. At this moment, my near horizon is crowded by another unexpected invitation to show a selection of work from Restless Earth in Berlin late May for the BBA Photography Prize Exhibition.

GALLERY

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Terri Warpinski explores the complex relationship between personal, cultural and natural histories through her lens-based, mixed media creative practice. Her current work, Restless Earth, draws attention to her home ground in the Great Lakes Watershed and the urgent necessity for ecological recovery, restoration and re-wilding in response to our global environmental crisis. For over four decades her various projects have taken her throughout the American West and Mexico, Australia, Western and Central Europe, the Middle East and Iceland. She was distinguished as a Fulbright Senior Fellow to Israel in 2000-2001, as Professor Emerita of Art in 2016 after a 32-year career teaching at the University of Oregon, was the Honored Educator of Society for Photographic Education in 2018, and most recently was awarded the Carol Crow Fellowship for Environmental Photography by the Houston Center for Photography in 2024. Along with being among the Critical Top 50 for Photolucida in 2024, she is a finalist in 25th Julia Margaret Cameron Awards in Barcelona, and a finalist for the BBA Photography Prize 2025 in Berlin. Her extensive exhibition record includes the Houston Center for Photography; Pingyao International Festival of Photography in China; the U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem; Houston International Fotofest; the Center for Photography in Woodstock, New York; the University of the Arts in Philadelphia; The PRC in Boston, and Camerawork in San Francisco.

She was awarded a DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst) Fellowship to Berlin to begin her long-term project Death|s|trip. The numerous artist residencies that she has been awarded are include: SIM in Reykjavik, Iceland; Scuola Internazionale di Grafica in Venice; Playa in Summer Lake, Oregon, and the Ucross Foundation in Clearmont, Wyoming. Her limited-edition artist books (Sagebrush, 1999 Surface Tension, 2016), and collaborative broadside portfolios (Liminal Matter: Fences, 2017 and Liminal Matter: Traces, 2018) with Portland poet Laura Winter are in numerous public and special collections including Stanford University; The Bancroft at UC-Berkeley; Beinecke Library, Yale; Book Arts Collection, Baylor University; Amherst College; and the Getty Research Institute. She is a member of the Environmental Photography Collective www.environmentalphotographers.com.

A native of Northeastern Wisconsin, she received her B.A. degree in Humanistic Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, and her M.A. and M.F.A. from the University of Iowa. Prior to joining the faculty of the University of Oregon she taught at the University of Florida. She once again resides in the glacially carved landscape that is ancestral home of the Ho-Chunk (Hoocąk) and Menominee (Kāēyās maceqtawak) Nations along the Fox River in De Pere with her husband, David Graham, where they founded newARTSpace.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Kirchoff is a photographic artist, independent curator and juror, and advocate for the photographic arts. He has been a juror for Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and has reviewed portfolios for several fine art photographic organizations and non-profits in the U.S. and abroad. Michael has been a contributing writer for Lenscratch, Light Leaked, and Don’t Take Pictures magazine. In addition, he spent ten years (2006-2016) on the Board of the American Photographic Artists in Los Angeles (APA/LA), producing artist lectures, as well as business and inspirational events for the community. Currently, he is Editor-in-Chief at Analog Forever Magazine, Founding Editor for the photographer interview site, Catalyst: Interviews, Contributing Editor at One Twelve Publishing, and the Co-Host of The Diffusion Tapes podcast.

![Ground/Water [Sensiba], 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64ab04fdab48185206d120e7/1746896332321-OB1VWN0KLHDB4FUTRZTA/2.+Warpinski_+Ground_Water_Sensiba_2023.jpg)

![Shelter [Oak Road], 2024](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64ab04fdab48185206d120e7/1746896334400-I1BCENCSN2PRO6MH47GE/4.+Warpinsk_Shelter_Kangaroo+Lake_Searing+Install_2025.jpg)

![Ephemeros [Sensiba], 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64ab04fdab48185206d120e7/1746896415146-QQI2M3RAWL3UNNWXNTPZ/6b.Warpinski_Ephemeros_Sensiba_+2023_HCP+installation+view_2024+.jpg)

![Enfold [Heins Creek], 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64ab04fdab48185206d120e7/1746896488411-COGSXWEWP7WC5UFSJ0BV/8..+Warpinski_Enfold_Installed+at+the+Hardy+Gallery._2023+.jpg)

![Ground/Water: Floodplain [County Road K], 2024](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64ab04fdab48185206d120e7/1746896490964-S99HU8WE6QQEJLDWJEPX/9.+Warpinski_Ground_Water_Floodplain_County+K_2024.jpg)

![Ground/Water [Kangaroo Lake], 2024](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64ab04fdab48185206d120e7/1746896589216-5IB68RB62REWI6X805DZ/12.+Warpinski_Groundwater_Kangaroo+Lake._Detail_as+installed+at+Lawton_2025.jpg)

![After/Image: Niagara Escarpment I [Below Bay Settlement], 2024](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64ab04fdab48185206d120e7/1746896491462-OEHHPWVY1YJ6RW4BC07R/10.+Warpinski_Afterimage_Niagara+Escarpment_2024.jpg)

![Ground/Water: Escarpment II [East River]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64ab04fdab48185206d120e7/1746896847693-NC96C00RA5PFCSILCLBJ/20.+Warpinski_Ground_Water_Escarpment+II_East+River._2025.jpg)

![Land/Trust: Field Study for Recovery [Oak Road], 2023](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64ab04fdab48185206d120e7/1746896774764-Q09HELC68XXRQRT9G66D/19.+Warpinski_Field+Guide+for+Recovery_Oak+Road_2023.jpg)

San Diego-based artist Annie Claflin uses photography to navigate identity, mental health, and memory. In this interview, she discusses her series Undertow, which explores the fragile boundary between land and sea through altered pigment prints and distressed photo-objects. By submerging, warping, and weathering images of the San Diego coast, Claflin evokes the erosion of memory, place, and self in the face of sea level rise.