Interview: Photoworks SF - Analog Photography in the Digital Age

Newcomers to the analog photography world often forget how prevalent film photography was through the late half of the 20th century. Through the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s, everyone processed film: Costco, “pro labs”, drug stores, and hundreds of small one-hour photo shops across the country developed film and produced prints for amateurs and professionals alike. There was a place on every street corner that offered a varying degree of photographic products and few stood out from the crowd as the place to have your processing done. At the time, the industry was full of businesses capitalizing on the popularity of the one-hour photo business model with no true dedication to the medium. They were simply in existence to produce income for their owners.

Fast forward to 2019 and digital photography has come close to wiping out film photography altogether. Though the medium has had a resurgence in recent years, we often have short memories of how tough the previous decade was on our beloved art. During the 90’s and early 2000’s, we saw an immense amount of hardships for the companies producing film products and businesses that supported them. ln 2001, the Polaroid Corporation declared bankruptcy and sold off its brand and assets, and in 2004, Ilford went into receivership. Though both brands have been saved by passionate film photography lovers, the last decade has been a scary time for analog enthusiasts and store owners. The changing landscape of our industry has resulted in just a handful of reputable labs developing and processing film across the country. One of these last remaining analog photography strongholds is located in the Bay Area of California, and they go by the name of Photoworks SF.

Originally founded by three partners as a one-hour photo lab business in 1987, Photoworks SF is now one of the West Coast’s premier film processing and printing labs that also offers a fully interactive digital imaging facility. Over the last 32 years the store has evolved and morphed into a place where analog photographers from all over the world call home. Though Dave Handler and staff have built a reputation for producing some of the best analog work in the world, it has taken years of evolving and changing with the industry to stay in business. To say they are a small business survival story would be limiting, as they have put their blood, sweat, and tears into holding onto their legacy while still keeping their doors open to professionals and enthusiasts alike. We had the pleasure of sitting down with Dave to talk about the last three decades of Photoworks SF, how they have survived, and his thoughts on the resurgence of analog and film photography as we approach the second decade of the 21st century.

Before you read on, Analog Forever encourages you to visit their website and try their services. We promise that you won't be disappointed! We have had our own film processed and scanned and we endorse them 100%! Check them out now at www.photoworkssf.com!

Interview

Michael Behlen: Photoworks SF was established in 1987 in San Francisco. What was the catalyst and process for launching your photo lab and business at that time?

Dave Handler: The original partners whom I worked for in a previous business (I was a video store manager), decided to open a One Hour Photo Lab as a pure business move, not as a labor of love, and I was hired to run the shop. We got started by the owners purchasing a "one hour photo" package: which was a film processor and photo printer and immediately sending me to a one-week course at a school in Minnetonka, Minnesota, operated by the equipment maker (Copal) which soon became Agfa from Germany. During that week I learned to operate the machines and all the little items that surround developing film. I learned to mix chemicals, and also how to monitor their stability, the same chemical monitoring is used today. In regards to ownership: one original partner remains, Mike Josepher. I bought out the other owner about 5 years in.

MB: How did it feel to become co-owner after managing the store for 5 years? How was this decision made?

DH: I have never been great managing by committee, and I had some ideas about the direction of the shop as more of a lab. The original partner wanted a portrait studio added, and I thought that would fail. As I had the lab skills, I was able to assert myself and eventually, the other partner moved away to another business. It's been just the two of us of since then. At the time, my parents sure were happy. Up until then, my mom thought I was a photo clerk at a Walgreens store. I really had no issue with technically having some ownership, as I've always wanted to better myself and it felt like a natural progression.

MB: If you had to say: what was Photoworks SF original objective in 1987? How has your store changed over the years since you started this journey?

Originally it was just a business, but as we got into it we realized the breadth of the photo community. The notion of One Hour Photo quickly morphed into a hybrid shop, serving all types of photographers. We decided to build a professional shop that was accessible to all. In and around 1989, pro photo labs were horribly snobby, known as "commercial" labs, they were not very welcoming to artists or anyone with a need that was beyond needing a quick snapshot developed. We landed in the middle. After I became an owner, we started to see more professional business and photographers start coming in, and one day I just pulled the ugly ONE HOUR PHOTO sign out of the window. We wanted to be more upscale, so we had to alter our perception. Putting in a darkroom and offering custom prints helped with that.

At our peak in 2000, we had 56 employees in three buildings, a dozen photo printing machines, and eight darkrooms. It was an army, and we processed 500 rolls of film a day, seven days a week. I even got into the headlines, most notably was my quote “On the seventh day, God rested, what a wimp." I got in some trouble for that, but we processed lots of film on Sundays! When we added black and white machine prints, our store really took off because wedding photographers became our main clients. We attracted even more of the business by creating our calling card at the time, "the “sloppy border”. It was a black rough edge on the print created by filing the film carrier and it made the pro's and everyone else’s prints look arty. So, it took off as an alternative to border-less photo prints. We even had an add-in The Yellow Pages saying "home of the sloppy border." This full frame machine print was a big deal. Photographers built their product around this, as previously you had just contact sheets and custom prints, now we had arty machine prints with borders.

Even though that became our bread and butter, we have always tried to serve everyone, and make the shop all accessible to all regardless of skill, no project too big, no project too small. Over the years we have kept adding services to keep up with customer demand and have adopted more technology and a wider array of photo display options while keeping our analog roots.

MB: For 28 years you have seen the industry change. How has the digital transformation of the industry affected Photoworks SF and how have you evolved with it?

DH: When digital hit, it was like an earthquake. At first, we held our ground and I rejected the whole notion as a fad. I even made a t-shirt that said "digital smigital". One shop I knew of immediately went high tech, spent a fortune doing so, and went broke. Digital was daunting and expensive and I thought I should stick to what I know. I hate not being an expert, and in the early days, digital was too much of a grey area with too many people figuring it out on the fly. I remember when some kid came back from Burning Man with a bunch of digital files to print. He said to me, "Hey Man, digies in the future and you better get with it". At that moment I knew that in some way, it was a fad that would eventually top out to some extent.

The advent of online printing really hurt us too. We lost a ton of wedding business to a company founded in 2004, called Pictage, that was able to give photographer's websites to preview and print images online. So they clients stopped printing with us and that hurt us badly. We had some lean times but survived it by ironically adding our own digital printing when the time was right. I transitioned into the digital realm very slowly, but it was difficult at first, as no one knew how to print digital files. I hired some tech people, but that was a mistake as they only knew computers. We tried for a while to emulate them and built a similar system, but eventually abandoned the concept. I made a decision to hold on to our analog equipment for as long as possible, but the machines were hard to maintain, and the vendors stopped making parts. Even the darkrooms dried up.

Gradually we upgraded to digital printers, but the key thing is that we always kept the film machines running, and our printers still using silver halide chemicals. Even today, our customer’s prints made from digital files are processed through traditional photo chemicals. I try to explain to people that we make silver halide photo prints and some people dig it, but some don’t care. I still use it as a selling point though: I say " that if you can smell chemicals, then you are in the right place.” Of course, we finally added an online store to make uploading files and purchasing prints pretty easy and that is working well for us. Nowadays, we welcome all types of media, and provide all types of products made from film and digital, it does not matter the source as long as the end products are there, be they photo prints, metal prints, wood prints, and/or custom framing.

MB: Many people have noticed a resurgence of film photography, especially on social media. Have you noticed the same? How has the recent craze been advantageous to PhotoWorks SF with hashtags like “believe in film” and “print your work”?

DH: Film never went away, it was just discovered by a younger crowd who grew up on tech. Instagram, with it's early "film" filters, it sparked something in people wanting to know the source of that film look. So began the whole ironic "I'm new to film" craze. All these hashtags make me laugh, like the hashtag, "believe in film". Most of my peers never really stopped believing. Though it has become a rallying cry, to me, it's just like any other art form. Though I can't say that I'm a fan of what social media has done to photography, I think the youth are embracing something special, and in some ways have brought back the whole film industry, so I go out of my way to be helpful and teach where I can.

I think the new shooters feel like they are part of something special, and they are keeping analog going in a world of digital overload. I'd like to think that the new shooter wants to "slow it down" in contrast to their hectic lifestyle, film makes you calmer and takes patience. I would also give the new analog shooters some credit for wanting to learn and appreciate the process. To me and I guess many others, "instant gratification" is an oxymoron. It seems to me that you need to make more than a 10-second effort to be gratified. There is a magical quality in the process much like vinyl records, you can feel the art when it’s tactile. There is nothing like holding something in your hand, the tactile sensation of an image on photo paper, even an image on inkjet paper, is a beautiful thing. I print my own work and proudly display it in my home. To be corny, you need to leave behind a physical record of your work; your images, it's your life. I have shot Polaroids of my kids since they were born (13 years now), and I have a wall in my house of their life progression. I could not live without it.

MB: What are your thoughts on the reinvention of Polaroid and the popularity of Lomography?

DH: I feel some kinship with the Impossible (now Polaroid Originals) folks because for years I struggled to maintain old film printing equipment. Our lab used to be all Agfa analog printing machines, the look of the prints from those machines helped put our shop on the map. One day without warning, Agfa went under, and we were stuck with a bunch of old printers and no support. I hired technicians to keep the machines going, but over the years parts vanished and eventually I gave up. Like every other photo lab, we bought new equipment. We still print from negatives but not before they are scanned first. You still see film grain, but it’s just not quite the same thing. When The Impossible Project was just starting we were a testing ground for their new films. Now that Polaroid is more or less back, I try and get my friends and anyone who will listen to dust off those old SX 70 cameras. Though Polaroid Originals could make these cameras a bit more affordable, as they were never intended to be so expensive, I would say they are keeping their roots. However, one thing that bugs me is that they can't resist marketing to the Urban Outfitters crowd. Urban Outfitters has decided Polaroid is cool, and so they sell it. Personally, I think teenagers should shoot Instax mini.

Lomography, on the other hand, has done some brilliant marketing and they make the great LCA camera. I can also say their 800 ISO film is a nice product. No one has branded analog as Lomography has and they deserve a ton of credit in my own opinion. Some say they are over the top, but I think people respond to their inventive films, which by the way, are now being copied by lots of homegrown small companies.

MB: Can you share with me the financial side of the business? What is it like operating Photoworks SF in the face of so many brick and motor businesses closing, especially in the Bay Area?

DH: I can only say that the financial pressure is off the charts because the cost of having a business in San Francisco is staggering. The hard costs like staff salaries (that allow them to live in the bay area), healthcare, rent, supplies, and insurance add up quickly. Though labor is the big expense, and it's a dance to keep all employees here happy: if we all get paid then I consider that profit. Beyond that, there is not much left.

The financial stuff never goes away because we know that we need a certain amount of volume to stay alive, so I am grateful for all of our customers. When we are busy all is well. It's just a matter of getting through a rainy February and March that is hard because I need to be able to keep staff at full-time hours, as we all have to live. At home, let's just say my family and I don’t eat out until Spring.

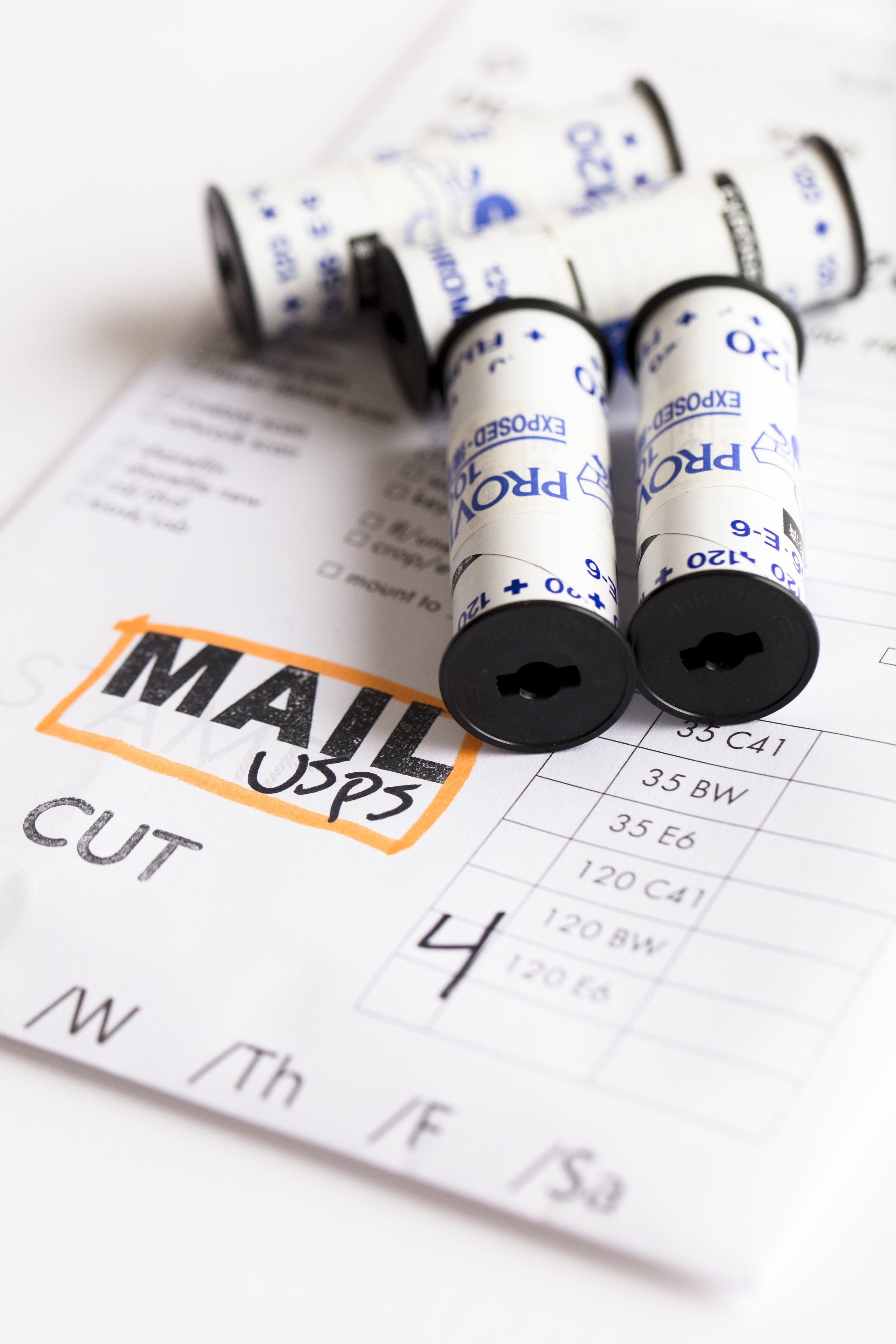

Luckily our storefront generates some good foot traffic. After all these years, I am still a huge brick and mortar guy, I have to be. I still see value in face to face interaction and I never take the customers for granted. While you can mail us film from afar, it's the locals that keep us alive. In retrospect, the best business model would have been to purchase a building back in the nineties, but we did not. Thus, we are locked into ridiculous rent payments. But this just means that we have to keep hustling to bring in new business. So far so good, but we always have to keep on eye on things.

MB: You shared with me that Photoworks SF is a business survival story. Can you share with me that story?

DH: About two years ago in 2017, we received a "notice to leave the premises” at 2077A Market/Church from newly installed landlords. After 29 years at our location, we were given 5 weeks to get out! The reason given was for an earthquake retrofit, which turned out to be valid, but the time frame to leave was just insanity. I went on the offense, threatening the new landlords with bad press, and they gave us an extra month to leave. There was a moment at which I thought, it's all over, we can't move. I started to search for a new spot, and things were dire. The locations we found were either expensive or in crappy parts of town. We even started searching the East Bay for a new location and considered getting an industrial space and becoming a mail order company. One day while walking in The Castro, I saw a new for lease sign on a furniture store, so I contacted the agent and got inside to check it out. It was a very old building, but it could be made to work for us. The only problem was that there were other parties interested. I had to lobby hard to get the space, but I used all my connections in town, and eventually, after lots of negotiating, we secured a ten-year lease, with a five-year option. The rent is high, but we have security, and as long as there is a photo industry we will be part of it.

Looking back, our old location was more centrally located at the intersection of multiple public transit stops. And though the earthquake retrofit was legitimate, the old building we were in was not safe and did need steel beams put it. Today, two years have passed and it is still vacant I try and not look back, but we had some crazy times in that little shop, with so many people coming and going through the years. I do think about how little I knew at the start, and how much I learned on the job. Yes, I yelled "fuck" and for a while, I thought this was the end. Of course, I soon swung into action and that’s why I am happy to say that our new spot at 2279 Market St. in The Castro is great. We are now located in a pretty building and allows us to look more like a gallery, rather than a shack. It also has larger signage that gives us way more visibility. We were a hole in the wall before, one that everyone knew about, but still a literal hole in the wall. I am glad we are now apart of this neighborhood. Though the actual Castro is two blocks up, there is a real community here that watches out for one another.

MB: How has being a small business enabled you to rise above your competition?

DH: You can always "ask for the owner" here. If you have a special circumstance, I try and help where I can. It's not a good precedent to give deals, so I have to be careful and pick my spots. We offer the student discount, and we do punch card loyalty programs as well. If you are printing an art show on a budget, I can help you choose materials that can save money.

I also help in other ways: I once went to an older man's dusty old house in Palo Alto who had just lost his wife and spent a day going through old boxes of photos with him. His family and friends were mourning and had to put together the photographs for the memorial, so I helped them do so. I did not charge to do this, but did ultimately scan and make a nice photo album for the man. He was very grateful and that made me feel worthwhile. The customer was really touched. I have been dealing with this for years, and we go all out to help people no matter the situation.

MB: What would you say Photoworks SF does "best"?

DH: What we do best is what we do worst....we do EVERYTHING. I can't say no because I want an all-inclusive shop that caters to everyone. That can be a problem because it's hard to be amazing across the board. However, I can say that film is still our mainstay, but working with the corporate world on larger design projects have helped pay the bills. I would have to say that if film went away, that we would be finished.

I like to think I am an authority on all things analog. I still love showing people how to load their cameras, explaining simple concepts, push/pull, etc.. I get a kick out of people making double exposures and then getting 5000 people to say "dope" on Instagram. That was never my motivation, and to think of it, the best photographers work off the radar IMO.

MB: Do you have a definition of what constitutes “true photography” and what do you think makes a compelling photograph?

DH: Everything is up to interpretation and everyone is entitled to make images and participate in the analog culture. You have to at least own a film camera once in your life. You need to have an understanding of the basics of composition, exposure, and how a camera works. Pretty simple stuff that everyone should at least try to understand, after that you can do whatever you want. A compelling photo to me is one that has either lots of depth, as in depth of field and multiple subjects. I love anything cinematic, as I'm an old widescreen movie fan. I do like a photo that tells a story, but on the subtle side, make the viewer of the image delve into things a bit. I do not like overt, in your face imagery. Just me, I'm sensitive. Double exposures, on the other hand, are fun, and worthy. I admire the people who are able to plan out the exact placement of the images, that's not so easy. I may have bad mouthed this at some point, but I've come around. Even random Holga shots are fun, I'm up for experimentation as long as you know the basics first.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Behlen is a photography enthusiast from Fresno, CA. He works in finance and spends his free time shooting instant film and backpacking in the California wilderness, usually a combination of the two. He is the founder of Analog Forever Magazine. Connect with Michael Behlen on his Website and on Instagram!