Featured Photographer: Nettie Edwards - "Grave Goods"

At its core, Nettie Edward's work is about death. But, then again, isn't most art? When I first came across her enigmatic object-based images they had been retweeted into my timeline with the intriguing title, “Grave Goods.” I immediately needed to know more about what I was looking at and how they came to be. Comprised largely of photograms made in the anthotype and chlorophyll processes, they don't necessarily strike you as being photographic in the modern sense. However, they connect you with an idea of the past, of memory, and of loss.

Anthotypes, made using an emulsion of natural materials, often flowers or fruit, are exposed in the sun until the highlights bleach away under the UV light, leaving a positive impression in its wake. Chlorophyll prints are a related process where the image is exposed directly onto a leaf, rather than a piece of coated paper. These processes are, by their very nature, transient. From the moment of their creation, they are in a state of constant decay. You can try to intercede on them to extend their lifespan with fixative sprays and UV filtering glass, but the images will inevitably continue their slow fade into obscurity. For Edwards, it is this very impermanence that makes these processes so fascinating.

“I knew when I took up this work I was going to be working with an ephemeral process, that was very much at the center of it. I wanted to explore my relationship with that impermanence. It became key to what I was doing and key to the conversations I would have with people who came to visit my studio and garden. It was a real shock to discover that people had very emotional responses, and it was a real gift. I think the making of ephemeral images, and the acceptance that the images are not going to last forever, it brings up lots of interesting questions. I feel that despite the challenges of working with the process, of working with impermanence, I think there's still so much to discover, to uncover, and to explore. It's enriched my practice deeply to say, 'I'm going to work nature's way, I'm going to explore what that means too me.'”

If there's an artistic equivalent of a farm-to-table restaurant, it might just be Edward's studio. Near her home in the Cotswolds she has two allotment plots where she grows the flowers and plants which find their way into her work. From seed to print, start to finish, she nurtures every bit of the process herself.

“It changes your relationship with the work because they're my babies! Now I find myself looking at flowers that I've grown and I'm not sure if I can actually crush that up. I find it increasingly difficult. I grow food and I eat it, but there's something about a flower. It's so beautiful, it's so perfect, and it's also not just mine. It belongs to the bees and the birds, it belongs to other creatures, so this isn't just about me, it's not just my resource. My relationship with them has changed, especially as I've been working with things I've grown myself.”

When Edward's aunt died in 2017 it was left to herself and her sister to clean out the house, a hoarder's maze of memories and trash. Being the family historian she felt that it was her duty to make sure nothing of interest or importance was thrown away and would find photographs, notes, and bits of historic ephemera amongst the rubbish. For a month she worked through the dust-covered piles that made up what was left of her aunt's life.

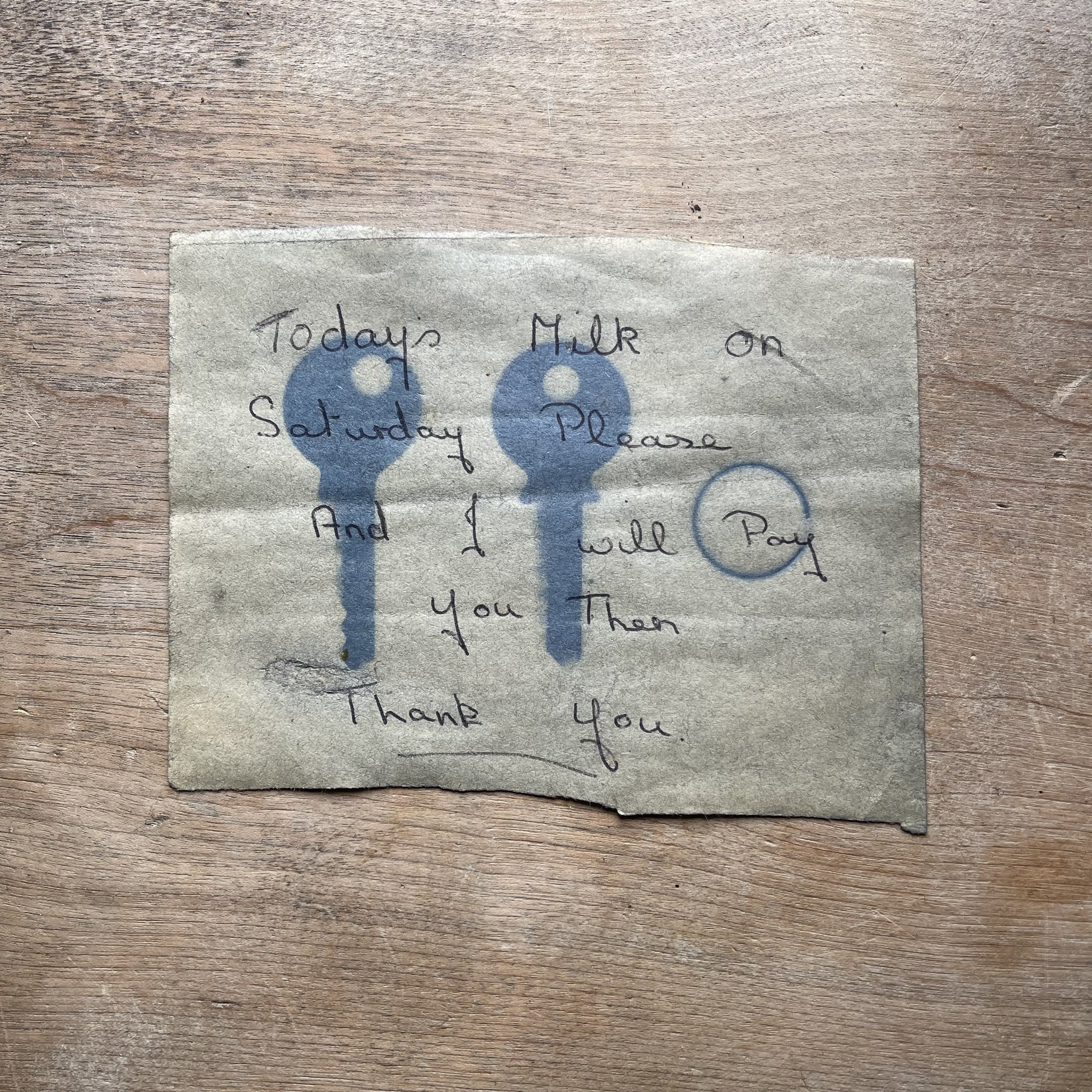

“I became fascinated by all the bits of paper and the notes. Here were the total evidences of someone's life. What do you throw away, what's important, what's irrelevant? It seemed to me that to find a till receipt from 1972 from a shop in Herefordshire, that's her life, that's an ephemeral moment, and yet that moment's been preserved. I became rather attached to these things and rather than chuck them all away I started to put them into bags to take home with me. I came home with bags of rubbish. Bags of envelopes, bags of letters, you name it. There was a purse with a moldy old sweet inside it, and a nail file, and a key, and I thought that each one of these things is a museum of somebody's life, specifically a woman's life in the 20th century. What death does is it strips us bare, and everything is laid out for others to make sense of.”

These rescued items sat in her studio until the first summer of Covid lockdown when she decided to revisit the motley collection and start to make peace with it. “I started to catalog it first: there are all the hair clips; and there are all the sewing sets.... But I started to feel I was losing the essence of my aunt's life. It's not about how many pens you had, life's complicated, life's a mess. I started to look at them like, that's a bus ticket, that's a nail file, they're two parts of somebody's life and if I bring them together it's a shrine, it's a memento. I suppose it was a way of letting go, as well. It was a way of working with the photographic process as a performative act. It felt fitting to use the anthotype process so that these images will eventually fade and vanish. It's an act of remembrance and then letting go.”

In “Grave Goods” the very act of constructing and printing the image became part of the meditative reflection on letting go. Disparate bits of a life would combine into a moment of creation, but with the foreknowledge that the very creation is itself transitory. Scribbled notes on a scrap of paper could become a printing surface, perfume could go into an emulsion in place of alcohol, a paperweight could become a contact frame. Brought together they can form their own little altar to memory.

“I found the anthotypes printing themselves to be as interesting as the final prints because, again, that was like creating a reliquary of someone's life. I became interested in the print in progress as an object to be considered. I think there's some beautiful metaphors to be found in that.”

Edward's aunt had also been married to an amateur photographer, and Edwards saved his archive of slides and negatives, full of people she didn't know and places she had never been, from ending up in the tip. This photographic ephemera contains formats that have become obsolete, the people are presumably long gone, what is left is the impression of a memory that isn't one's own. She began to experiment with these bits of lost photographic past by printing them on leaves from her garden, which became a sister series she calls “Taken From Memory.”

“I started by printing the slide carriers or the bits of film that have just got light leaks in them. That's light from another time, and I love that. It became a process of recycling light. It's using something that's been created with light in the past, it's past light that's trapped in that piece of material and then I'm using the light of now to make a new version of that image. I'm going to reprocess these photos and they'll disappear again.”

Photographs have an interesting hold over our current ideas of memory and permanence. We have this expectation in our minds that we can create this permanent document, a definitive record of something that happened, of something which existed. From the second we invented fixer the photo industry became fixated (pun intended) on longevity and preservation and the promise that your images will outlive you. But, as an artist and as a historian, Edwards took a step back and wondered, what if I let go?

“I'm very interested in this idea of what we expect of photography, our emotional relationship with it. It's part of our sense of self, our sense of memory, who we are, and where we are. I am fascinated by the very visceral connection we have to the photograph. I describe it as a deeply co-dependent relationship. 'You're investing all this emotion in me and I'm just a chemically coated piece of paper.' It seems a bit unreasonable, really. I'm not making work for the future, the process is the thing. But as a professional artist you have to sell your work and show your work, so what are the challenges of that, and what questions does that throw up about our relationship with the people who view our work. This brought up a lot of questions about my professional life and a world in which we might work more sustainably.”

Ultimately, for Edwards, the act of making this work was about confronting loss, working through grief, and finding a closer connection with and acceptance of mortality.

“I think there's a role for photographic process to play in healing and in exploring these difficult subjects. It's also an incredibly life-affirming thing to do, to face that and to say that nothing's ever going to last forever. And that's kind of contrary to what we see the photograph as: its memory. It's not just a document of presence, it's a document of absence. I think as artists, or maybe just as human beings, we all want to believe that something's going to exist beyond us, that this is our legacy. I decided maybe it was time for me to put myself in the position where I am working with this process of loss. Here's a chance to actually face something and go with it and accept it. I always feel that if you embrace things you grow more than if you resist them.”

GALLERY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Niniane Kelley is a fine art photographer living and working in San Francisco and Lake County, California. A native of the Bay Area, she is a San Jose State University graduate, earning a BFA in Photography in 2008.

Drawn to photography for both the immediacy of the image making process and the intrinsic alchemy of the darkroom ritual, she crafts the majority of her imagery using traditional 19th century processes which give each piece its own unique character.

She teaches workshops in the Bay Area and surrounding environs. She most recently worked as a photographer and manager at San Francisco’s tintype portrait studio, Photobooth.

Connect with Niniane Kelley on her Website and on Instagram!

Analog Forever Magazine Edition 11 includes interviews with Robert Stivers, Chad Coombs, Binh Danh, and Susan Goldstein, accompanied by portfolio features of Amisha Kashyap, Vaune Trachtman, Montenez Lowery, Kayhan Jafar-Shaghaghi, Blake Burton, Michael Stenta, William Mark Sommer, and Beihua Guo.