Interview: Thomas Alleman - A Dreamier View

Born and raised in Detroit, Thomas Alleman has a varied and diverse skill set found in the trappings of a successful career in photography. Not initially succumbing to the visual arts, he graduated from Michigan State University with a degree in English Literature. Later, developing an interest in photography, he grew and learned his craft while launching a fifteen-year stretch as a photojournalist in San Francisco and Los Angeles, California. During these and subsequent years in the corporate and editorial worlds, Thomas continues making his living with camera in hand, all the while making images on the side that would develop into full fledged fine art bodies of work. It is this career that I wanted to examine in retrospect with an individual easily described as a photographers photographer.

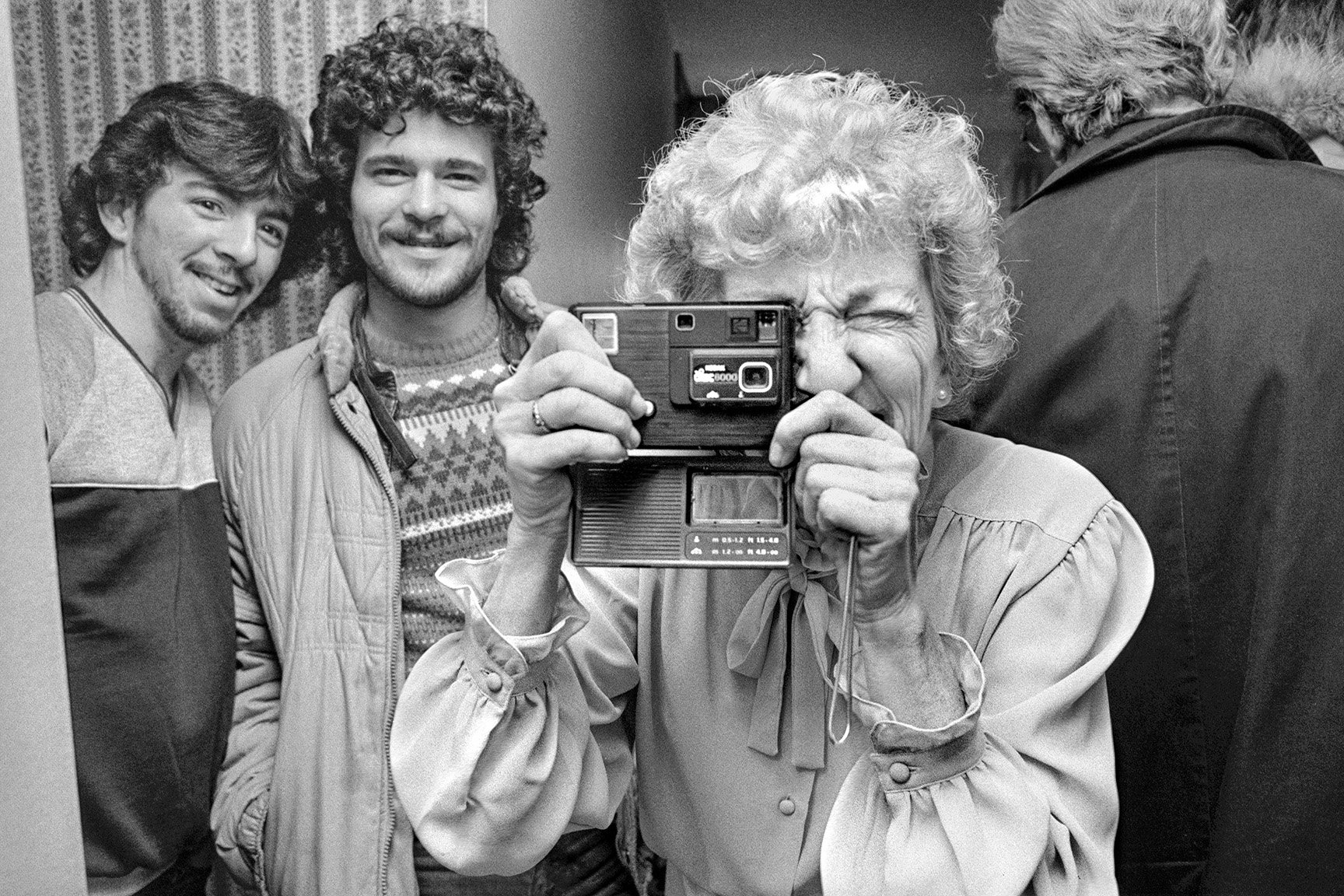

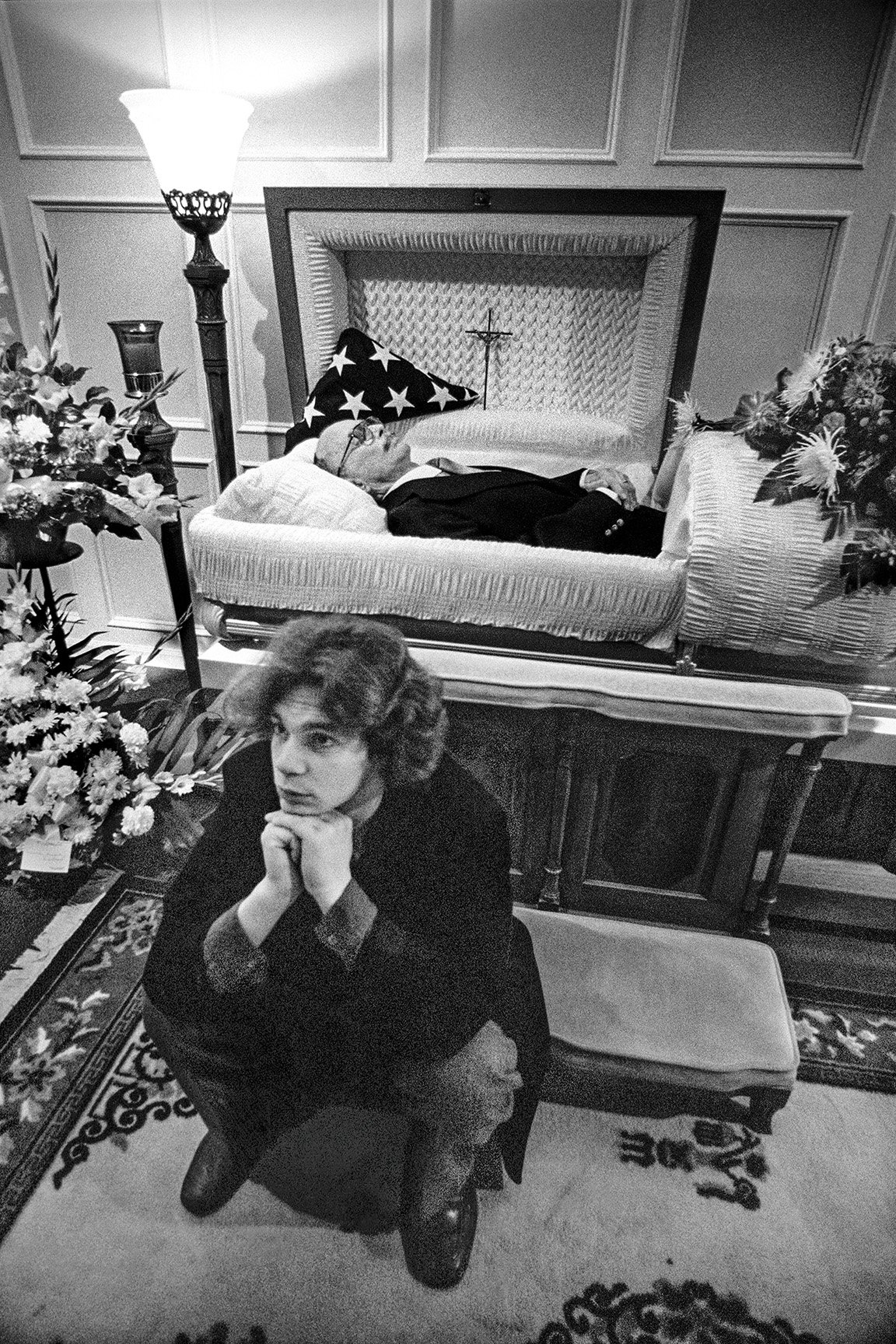

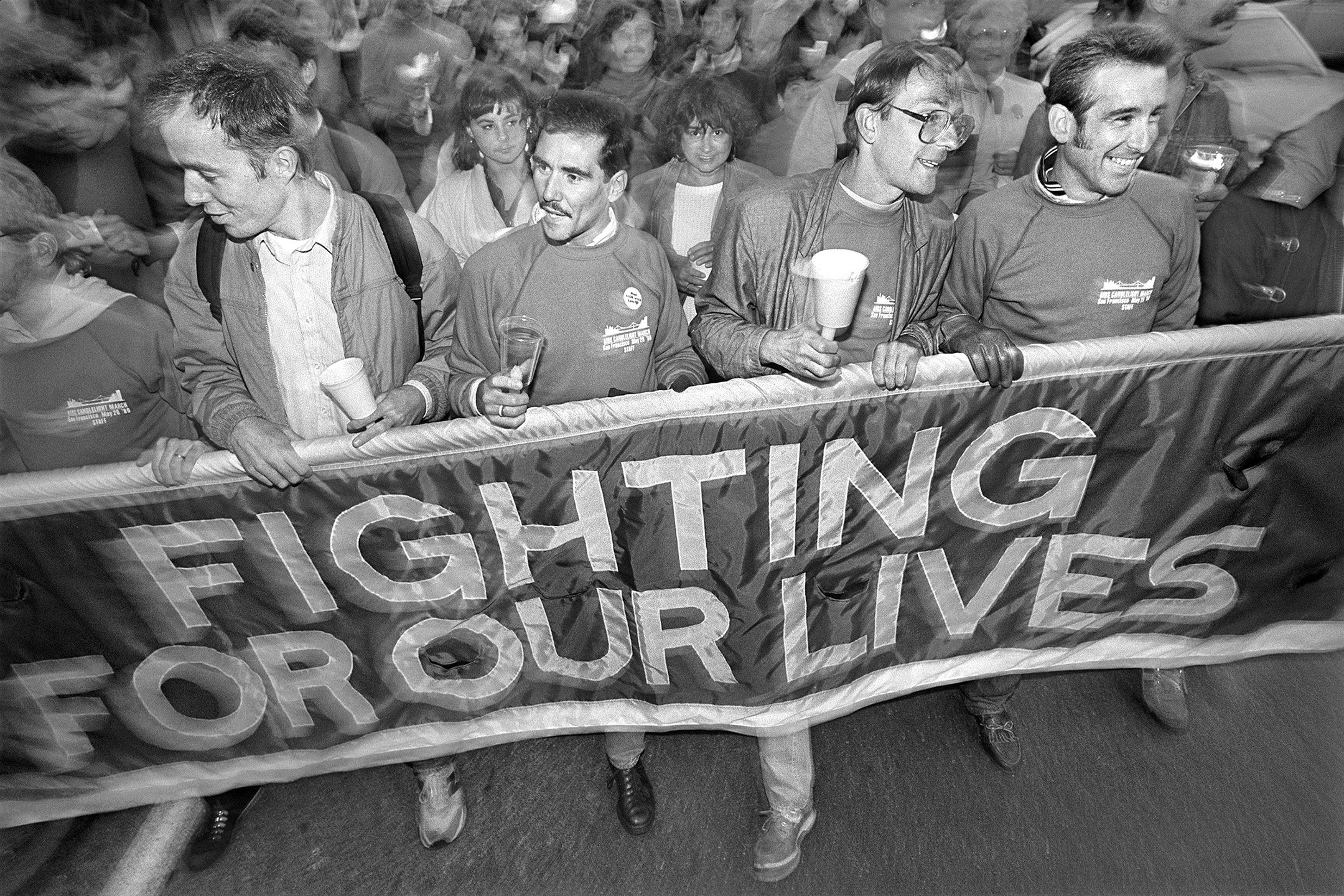

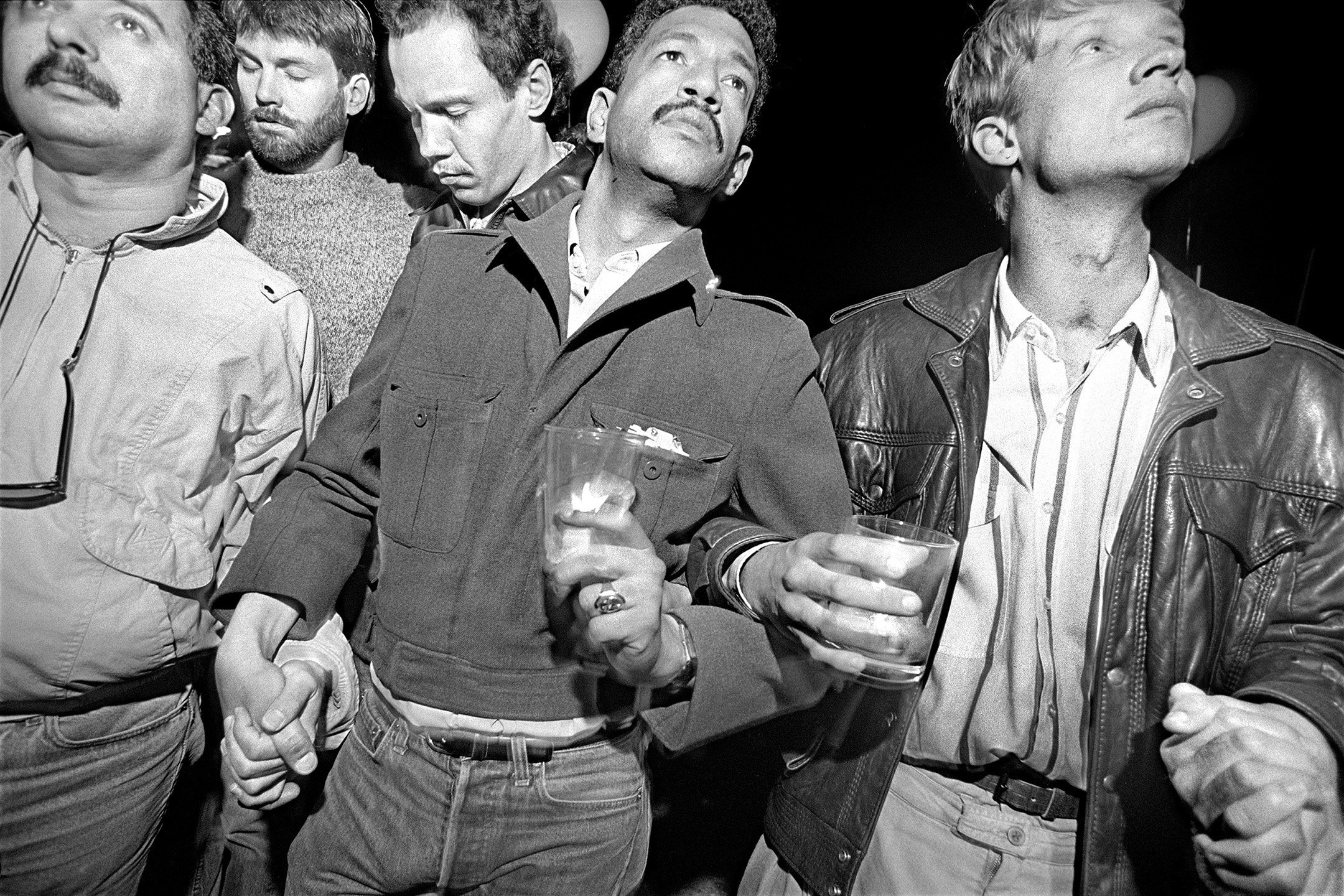

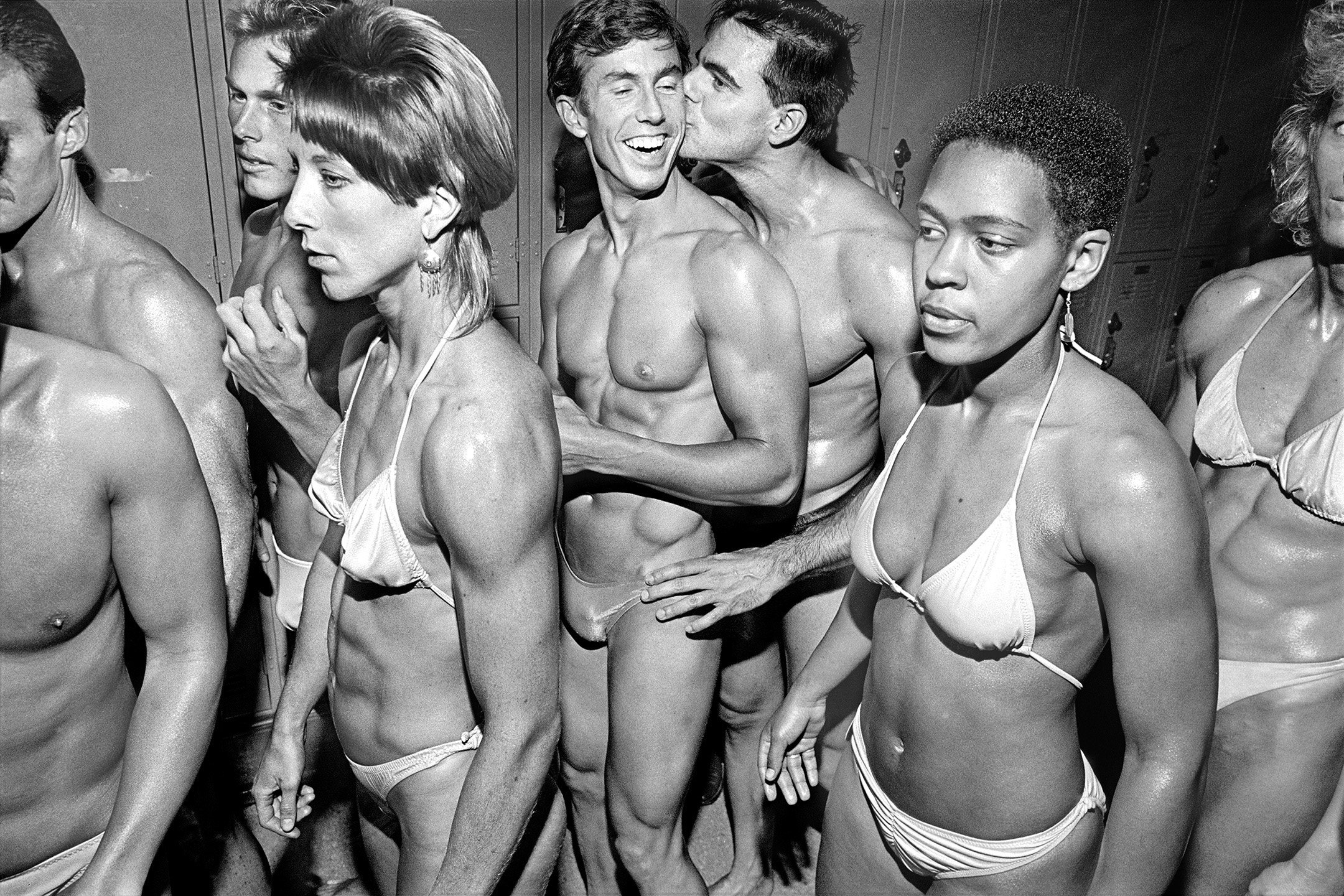

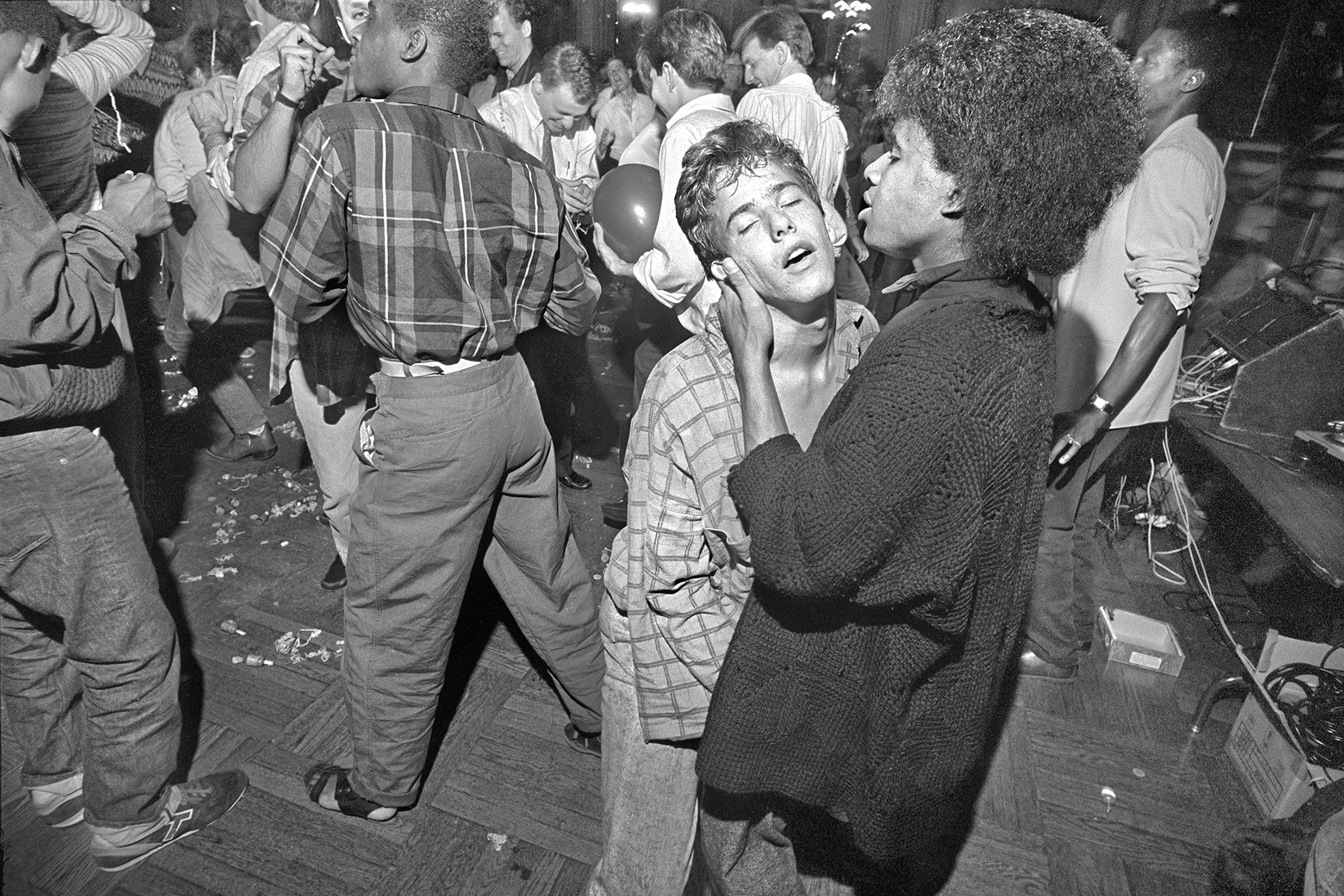

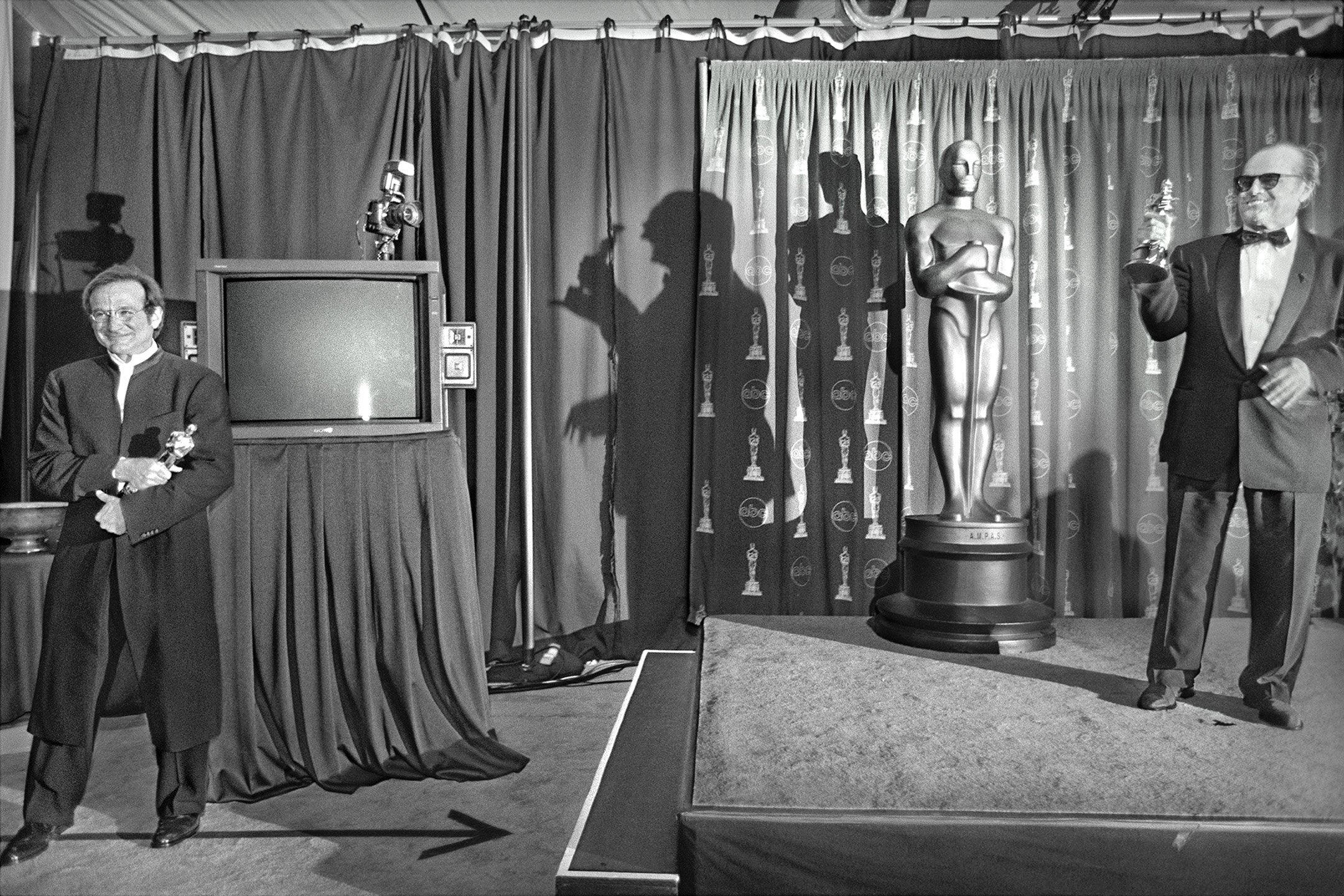

Making photographs for various clientele requires the ability to think on one’s feet, stay alert to your surroundings while being the ultimate observer, and perhaps most importantly, being a problem solver. One needs to not simply get in and get the photograph, but make it interesting and tell the right story at the same time. Much of Thomas’ early work makes these traits apparent while showing more recently exhibited images from his past. Pulling from a historical archive, still very much topical and relevant to today’s society, he presents photographs of his own American family in decline in “The Unwinding” — as well as imagery from San Francisco’s gay community during the height of the AIDS epidemic, “Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws”. These photographs, along with those from Alleman’s “Social Studies” work, continue to resonate with viewers today.

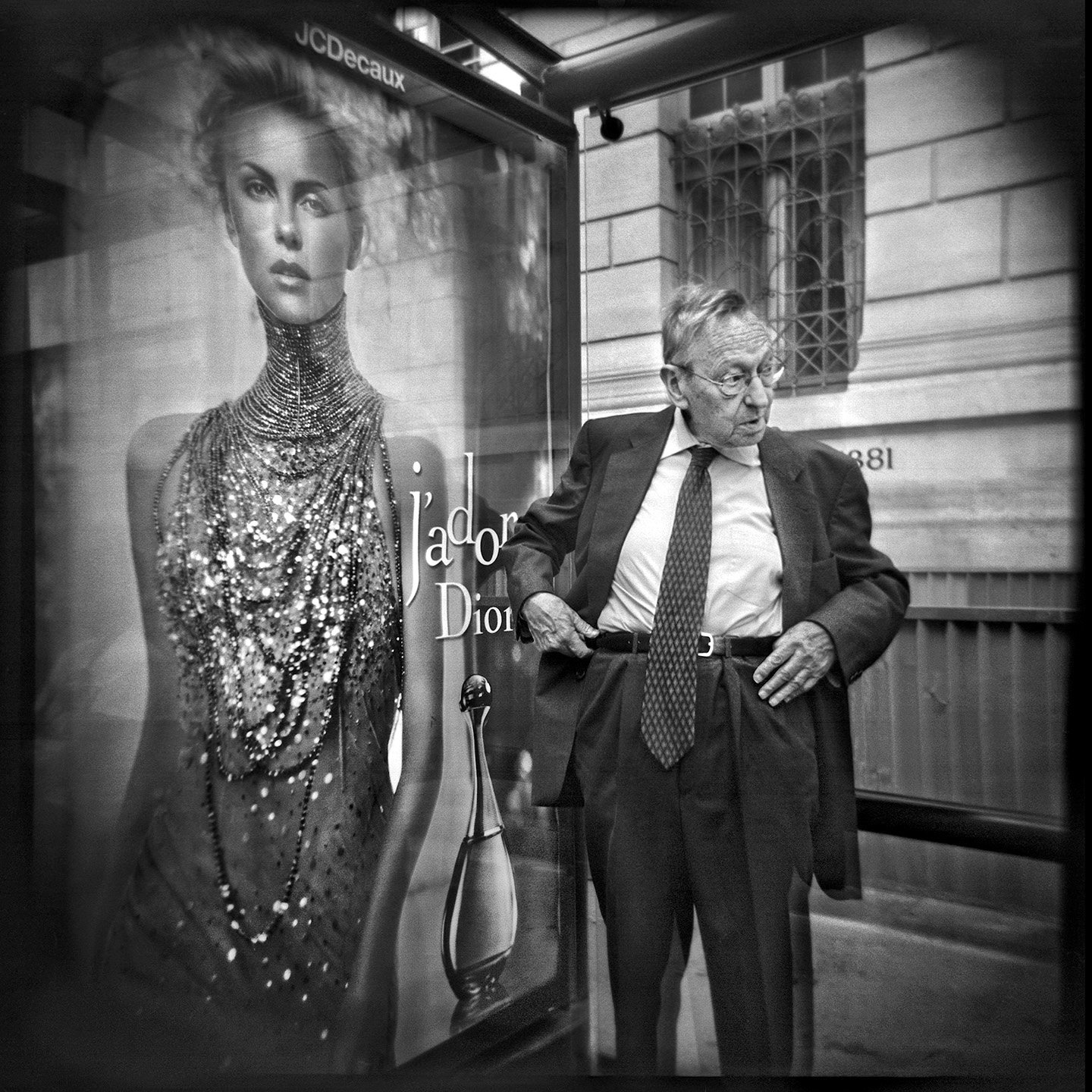

On top of all of this is Alleman’s long term and ongoing project, “Sunshine & Noir”. Of particular note to the film loving photographers of both yesterday and today, Thomas handily makes use of the low tech, plastic, Holga camera to accomplish this work. Filled with different emulsions of black and white film, he traverses and documents the urban landscape in search of the poignant, the humorous, and the sublime. Started in Los Angeles in 2001, his desire to expand this collection to an ever widening list of cities - New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Paris, Boston, among others - has led to an immense body of work that has proven difficult to bring an end to. With the prospects of introducing us to a monograph of the Los Angeles works, there is much to look forward to, however.

It is with good reason that Thomas’s affinity for pouring out knowledge to eager students in his workshops and classes is met with such high demand. He is without question the right person to educate and enlighten those interested in the photographic arts and careers of tomorrows image makers. One of the things I try to do here at Analog Forever is to express to those a need to develop ones “voice” and aesthetic, and to photograph with thoughtful intention. These are the tried and true practices that serve a photographer well. Thomas Alleman is just the kind of person whose personal tales and experience make these practices a road towards self-fulfillment. Any discourse with him is time well spent, and I am happy to present this interview to our readers at Analog Forever.

Interview

Michael Kirchoff: Tom, thank you for taking this time with me to answer some questions about your prolific career as a story teller and image maker. I want to ask a series of specific questions about a few older bodies of work that appear to have shaped your aesthetic, and then follow that up with some general questions about how and why you work the way you do. First though, it’s probably necessary for you to fill us in on how and why photography became your trajectory in life. How about some background on your start?

Tom Alleman: I was born and raised in Detroit, where my father was a salesman for trucking companies and my mother was, after a while, a sculptor and ceramic artist. I’m the oldest of three boys, all of whom came of age in the 60s and 70s. We lived next to a miles-long easement that the Edison company used for their high-tension towers, so we built ballfields and hockey rinks under those singing wires in every season, and our house became the headquarters for the neighborhood kids who played sports with us. We listened to Tiger baseball every night on the radio, and devoured books about legendary quarterbacks. But, when adolescence came we dropped all that in a heartbeat, mesmerized by the siren song of pop culture. We studied record jackets as we’d once pored over box scores, tore through the canons of Vonnegut and JD Salinger, memorized George Carlin albums, traded copies of the National Lampoon with our outre friends, and stayed up late to watch Marx Brothers films on the UHF channel. I got hooked by movies, and took a filmmaking class at the local community college when I was in tenth grade; with frequency, I skipped out of school and road my bike five miles on the shoulder of a freeway to see matinee movies at the four-plex; I read all the paperback tie-ins and screenplays I could find at the Little Professor Bookstore in the mall.

It was that obsession that motivated my first forays into photography: I borrowed a camera from the school newspaper and spent a week walking around with it glued to my eye, seeing what things looked like through a viewfinder, panning and swooping and “making movies” in my mind. The natural consequence was, the yearbook editor gave me some film and a list of shots she needed. Haltingly, I learned about lenses, exposures and enlargers---all of which I was quite ham-handed at. In university I pursued a couple classes, years apart, but they ruined my semester every time: I spent every night in the darkroom, tirelessly printing and reprinting the same negative, and blew-off my daytime classes for long drives into the farmland that surrounded our school, looking for abandoned barns and rusting old tractors to photograph. For those and other predictable reasons---pinball, pot, parties---I wrecked my education at that backwoods teacher’s college, and transferred down to Michigan State, a serious institution that demanded my best attention. Somehow, it didn’t occur to me that the little Minolta I’d been so smitten by could provide career opportunities---I saw it as a troublemaker in my young life, a dangerous distraction---so I placed it in a drawer and hunkered down for the serious pursuit of an English degree. Three years later I took it out again and tried to remember how to put film in.

MK: Your series, The Unwinding, seems to be a genuine and heartfelt start to a photojournalistic career. Was this more an exercise towards your future career, or a way of comprehending and dealing with the emotional struggles of your own family? Perhaps both?

TA: When I graduated from Michigan State in 1981, I had no useful skills or immediate prospects. I had a point of view, I suppose, and an attitude about certain material---I’d been an English major in a Creative Writing program---but I didn’t have the discipline, in those days, to do more than dabble at the standard wannabe stuff: acting and folk music and short story writing. I was a bit of a dilettante, a know-it-all who bussed tables and wrote desultory feature stories for the local weekly. By very slow measures, I started making photographs to accompany those articles, and, after a while, took up a search for examples of such pictures at their best. The Village Voice became a model---along with other lefty tabloids like Portland’s Willamette Week and the Chicago Reader---but I found my best inspirations at the library of the local community college, among a photo collection of about a dozen books. (In the pre-internet era, there was nowhere else to study the culture of photography, whether the commercial aspects or the history or the art of it.) Besides the requisite volumes of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, which were irrelevant to the faux-journalism I was practicing, there was a self-published anthology from Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand’s “Public Relations”, and one I’d seen floating around the art department at MSU: “Gramp” by Dan and Mark Jury.

Guided by Friedlander and Winogrand, I adapted a hand-held strobe to my kit and learned to tilt my frames, and discovered a natural affinity for that kind of off-center reportage---but it was the Jury stuff that really challenged and lured me. Their scruffy little photo-diary gathered the pictures they’d made while caring for their dying grandfather, a retired coal miner, during the last three years of his life. I wasn’t aware that, at that time, those images were somewhat controversial: such grim intimacy was rare, and frowned upon. I simply figured, “This is a thing that some photographers do sometimes.” Anyway, I wasn’t looking for controversy or a particular depth in my own work---I wouldn’t have known what that was, in those early years---but I did feel an affinity for that kitchen-sink storytelling, and I recognized the technical challenges the brothers had overcome, shooting Gramp in one dim room after another. To work in that world, if it ever came to it, I knew I’d need to hone my chops, and that blooming ambition to master the photographer’s craft was a personal development that pleasantly surprised me: I’d been waiting forever, it seemed, to find the humility to dedicate myself to task. To learn about “available light” and slow shutters, I practiced on my friends every night, while we played cards and drank beer, and, when they finally grew irritated and banned my camera from the table, I took it home with me to Detroit one weekend, to continue testing my techniques on the family there.

From the first, even as I labored and stumbled with my exposures of Mom at the dining room table, drinking coffee in the evening, I felt a strong, strange thrill burbling under the scene, and was confirmed in that feeling when I looked at the pictures on my contact sheet. I knew from my college lit courses that what I’d identified was “subtext”, the story beneath the story, that invisible narrative that makes sensible all the little data points that my pictures were describing. Apparently, my years at college, living among other folks, had distanced me from the family vibe, given me perspective on their habits and strategies, so that I could suddenly feel the machinery moving under the scenes they played out, and I could see the evidence of that in gestures and body language, which I realized was photographable. So that’s what that Minolta was for! Every time I came home for Thanksgiving or some birthday, I shot a dozen rolls, with the simple intent to improve my technique and try to catch a little whiff of that frisson I’d felt at first, the subtext that haunted those scenes.

For the first couple years, that subtext was supplied wholly by the past---my past, as a kid in that house, knowing those people and their foibles and fears and desires. My gaze was not particularly inclined toward the future, and the fate of the family; I wasn’t looking toward their demise. That my father was diabetic and had had heart surgery was “interesting” to me, and I’d certainly noticed a foreboding melancholy that played across his face sometimes, but it wasn’t until two years in that I began to imagine his immanent death, which turned my gaze toward the future as I traced his arc there. I saw Bob’s dopey high school alcoholism blooming in those coming years, and Mom’s cigarette-seared lungs growing weaker, and suddenly those recollections I’d seen in the shadows of my pictures became premonitions instead: the song had modulated to a minor key, and the Ghost of Christmas Past had surrendered the stage to the Ghost of Christmas Future. From 1984 onward, I was aware I was photographing an unwinding story, whose last act would probably feature Mom’s death from some gruesome malady of the lung.

On New Year’s Eve of 1990, I made my last exposure, and she died in July of 1991. I put those negatives away in a banker’s box, which I carried from apartment to apartment to garage to storage for over 20 years. Since 2013, I’ve been editing and scanning from that collection of about 400 rolls, and have prepared 80 images. As usual in such cases, I wrote an introduction to the material---the standard seven or eight pages---but, against all advice and better judgement, I’ve spent the last two years expanding that piece of writing far beyond the scope of the pictures. For better or worse, I’ve conceived and almost finished a “literary memoir” that tries to identify the seeds of their demise in the events that long proceeded my photography, and that traces the consequences of all that into the present time, almost thirty years after Mom died. It might be a ridiculous misfire, but for the moment it seems like a holy ambition. My Waterloo, perhaps, or my Dunkirk.

MK: I remember living just outside of the Castro District in San Francisco not long after you had photographed your series, Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws. It was an emotional time to be there, seeing so many celebrating their lives with the shadow of the AIDS epidemic always looming. Were you covering the people and the crisis there for a particular publication, or was this more a response to what you were witnessing while working in the city? Also, it seems as though this is a project you are only recently showing as a completed body of work. What has the reaction been showing this in a historical context?

TA: I moved from Michigan to San Francisco in 1984, to see if I could get a photojournalism career off the ground. But I was ambivalent, to say the least, about the super-straight, fly-on-the-wall stuff that was then orthodoxy in the newspaper world---I was too weird and unruly, and wanted to state a point-of-view in my pictures. My portfolio showed that reticence: no football shots, no houses ablaze or cops-and-robbers, but several flash-lit, flatulent views of moping cheerleaders and leering punks. None of which endeared me to the handful of bewildered suburban editors I met with. I realized, yet again, that I probably wasn’t cut out to work at the center of the dominant culture, but rather at its edges, hectoring the squares from the outside. (While looking to the day I could seize their attention on my own terms, of course.) Touring those edges, I ended up in the Castro District, where I discovered the Sentinel, a sharply-designed gay weekly that reminded me of the Village Voice. In fact, when I met with the Sentinel’s editor a couple days later, he stopped halfway through my portfolio and fixed me with a wily eye, saying, “My boy, I think I’ve finally found my Sylvia Plachy.” Ms. Plachy, of course, was the Voice’s most famous contributor, a Hungarian photographer who’d been mentored by Andre Kertesz himself, and who shared the master’s lyrical vision and wide-ranging technique. I took a couple assignments, won the front page twice, shot a couple more, and ended up spending three years in the heart of San Francisco’s gay community, just as the first wave of AIDS and HIV was crashing onto Castro Street.

In a neighborhood like the Castro, where everyone confronted disease and death every day---their own, their lover’s, their neighbor’s---the Sentinel chose to spare its readers too many stark depictions of the horrors that all were numbingly aware of: the lesions, the abattoir at San Francisco General Hospital, the gaunt young men with their oxygen masks. Instead, I was persuaded to photograph the public, communal response to the epidemic---which I was entirely prepared for, having learned my moves from the books that William Klein and Garry Winogrand and Chalres Harbutt had published. Every week I shot demonstrations, sit-ins, protests, marches, and parades. On the social scene, which still thrived, it was drag shows, lip-sync bacchanals and Halloween carnivals. As the Voice did in New York, the Sentinel published my pictures big, always in their raggedy full-frame glory, surrounded by aggressive, expressive type and blocks of color. At those six-column sizes, the images could convey a ton of nuanced information, which encouraged my natural inclination to wide lenses and blasts of revealing strobe-light. But I set myself the goal of using that aggressive, pugnacious style to create images that were sympathetic, even tender, toward their subjects. Because, in that first age of AIDS and HIV, I was often photographing scenes---vigils and memorials---where sorrow overwhelmed the folks I shot, who certainly didn’t deserve an “ironic”, Weegee-styled presentation. I was often successful on that tightrope; the pictures that failed never made the paper or the portfolio.

The experiences I had during those three years on Castro Street made a real photographer out of me, and my gratitude for that opportunity is boundless. Personally, however, I was devastated by all that emotional calamity, the daily slaughter and the feeling of doom that’d crept into my bones. I kinda snapped after a while, and was pretty broke, besides---working for peanuts all that time. Brokenhearted, I fled to Southern California, and got a staff job at a small newspaper in Claremont, which paved the way, five years later, for work at bigger and better dailies in LA proper, and then a decade doing national magazines. The negatives from my San Francisco sojourn joined the film I shot of my family during those same years, all that 80’s stuff crammed into a couple cartons that I didn’t open until those subsequent careers wound down. I began the long slog, digitizing contacts and scanning work prints, in 2007, and debuted 53 of those images in 2012 at the Jewett Gallery in SF. That show was up for two months, and generated almost a hundred pages of comments in the Jewett guest book---an outpouring of testimony and recollection and cri de coeur that just flabbergasted and humbled me.

MK: In looking through your collection, Social Studies, there is an intimacy with your subjects that is so clearly defined, yet often unpredictable. This is a photographic style that appears to give your photographs a voice, beyond simply documenting events or your surroundings. Was this always how you saw things or is this a style that was developed over the course of many years of experience?

TA: I’ve realized, from running my workshops and classes, that everyone learns in their own way, and at different rates. Personally, I’ve always preferred to teach myself whatever little crafts or pastimes I took an interest in, from sports to music to writing. I bristle at instruction, and mistrust instructors, out of arrogance and impatience I can’t tame. (The irony abounds!) Learning by that solo route might, I suppose, preserve some of the unique passion that first motivates the student---it did for me---but it’s also a long, long road. When it comes to the basics of commercial and news photography, I’m sure I “wasted” three or four years, slogging through it on my own. But the trade-off ended up being a grand one: before I ever realized I needed to hone a diverse technique to get a newspaper job---learn about long lenses and depth of field, learn about shooting in low, available light---I stumbled onto “my picture”, the kind of image I was made to make, which I could acquit with the tools I accidentally had at hand, a Minolta SRT-201 with a 28mm lens and a handheld Vivitar strobe.

Based on a quick glance through some monographs I’d borrowed from the library, I spent the spring of 1983 mimicking the flash-lit, fractured close-ups that Winogrand and Friedlander and William Klein had made at house-parties, art openings and conventions. From the very beginning, I intuitively understood almost everything I needed to know about that kind of work: the strobe technique, the slyness and aggression, the use of that wide lens. More than that, I “got” the feel of those pictures, their anarchic attitude, the barely-controlled chaos. From studying my contact sheets obsessively---I slept with them---I realized that my most successful images were the ones that most disguised the nature of the event, that subverted the assigned narrative, and that the best shots filled the frame with disembodied shards of information, all equally valuable to the non sequitur the picture had become. I’d begun by aping those established photographers, but within months I truly felt I’d found a voice of my own, for the first time ever. I’d been despairing that I’d ever get a foothold on some genuine artistic practice, and then, almost overnight at the age of twenty-five, something had cracked open, and I knew I’d finally begun my real life.

I made those pictures for about two years in Lansing and Grand Rapids and Ann Arbor, during the same period that I was travelling back and forth to Detroit to practice a whole different documentary style on my family there. That was a heady, electric time for me, like I was on fire every day. After all that, puffed-up with newfound confidence, I headed out for San Francisco, and ended up doing similar work in the photojournalistic realm, making my strobe-y, wide-angle shots for weekly tabloids, like Sylvia Plachy and James Hamilton did at the Village Voice. That slow immersion in the culture of newspapers, and the access they gave to the kinds of scenes I wanted to shoot, persuaded me that I should try for one of those jobs. Easier said than done, even then! It took a couple years to master the fundamentals necessary to score my first full-time job, at a suburban paper down near LA, and three or four more to escape that podunk town for something bigger and better and closer to the beating heart of things. Near the end of that apprentice period, I woke up one day to the realization that I’d spent half-a-decade preparing for a job I barely wanted, and, in its pursuit, I’d set aside the one true thing that was actually special to me, and special about me: those cockeyed pictures I’d discovered at the beginning, the one’s I’d called “Social Studies”. I hoped I hadn’t lost the knack for that, which, for all I knew, might whither from disuse.

In the following months, I won a cool job at a daily paper in LA proper, shooting color with top-notch company cameras and all the lenses I could pack in a shoulder bag. And, on weekends, I rejoined “Social Studies”, using my bright new press pass to get in to conventions and galas and ballgames, to shoot those screwy black-and-white pictures I’d discovered at the start and loved all along. I did that for seven more years, until the urge ran dry and my newspaper career stalled; I leapt upwards into magazine work, and was distracted yet again by the vicissitudes of a weird and demanding career. Altogether, I spent seventeen years on “Social Studies”, and showed forty prints in a half-dozen locations around the states of California and Michigan. After that, I tended my new magazine clients for a couple seasons, until events shoved me toward “Sunshine & Noir”, my next way-too-long undertaking.

MK: In the midst of your professional career, you decided to bring a different look to your already defined style of working. Your use of the plastic Holga toy camera has enabled you to achieve this, by creating a multi-faceted fine art body of work known as Sunshine & Noir. Can you tell us a little of how this idea came about? Why a camera such as this for someone used to using modern cameras to create images?

TA: At the time I began my self-education---stalking monographs in the local libraries, collecting influences---the Magnum “style” and attitude were, I recognized, the essential mode of popular photography in the public realm. My aim was to document people in the world and in their daily lives, and, for the next fifteen years, the Magnum photographers guided me by their example. So, when Phaidon published “Magnum Landscapes” in 1996, I was floored and practically offended: those people-less pictures seemed off-mission and irrelevant and almost sacrilegious. What was the point of such a stupid book? To figure that out, I pored over it more than any of the volumes I loved best. Perversely, I set out make a series of my own landscapes, just to get a feel for the process, which several of those Magnum heroes had apparently embraced. What was the big deal? Of course, the punch line is: I began to enjoy that process myself, that way of seeing that sought out evidence of life in the built environment, in the immediate absence of living beings.

But, whatever pleasure I took from practicing that new viewpoint, the pictures themselves were underwhelming to me. In that pre-digital era, photographers wouldn’t see the results of their efforts until they’d processed and printed their film, so they needed to believe with some certainty, before they ever left the scene they’d been shooting, that they’d made and acquitted all the right choices about lens, exposure and vantage point, and that they’d gotten the best results possible from that situation. In many cases, one would never again have access to that scene, nor certainly that slice of time. I’d mostly mastered those moves, after ten years as a professional, making publishable pictures on demand every day. Practicing my Magnum landscapes, I’d felt excited about the scenes I stumbled onto, the strange juxtapositions and dense arrangements of stuff---buildings and fences, vacant lots and neon signs and lowriders at the curb---and I’d been perfectly confident, in the moment, that my compositions balanced sturdiness with surprise, confirmation with revelation, and that my technique was impeccable. So, I was bewildered, then, that those qualities seemed utterly insufficient to my intentions, that my contact sheets from those first months of shooting were so unsatisfying to me.

I wondered if my camera format was the culprit: I’d used a pair of Olympus 35mm bodies, with 28 and 50mm lenses, to shoot those black-and-white images. Perhaps, I thought, the dimensions of the 35mm frame, or its long-ish depth-of-field, were too hackneyed, too predictable and pedestrian for what I had in mind. I returned to the field with a Hasselblad in hand, and spent several weeks reshooting those same scenes and streetcorners, but felt an even greater let-down when I examined that next set of proofs. What was I doing wrong? Once again changing-up the dimensions of my frame and the depth of my focus, I went back into the breach a final time, reshooting a dozen favorite spots with my Graflex Super-D, a reflex 4x5. When those big negatives failed, as before, to embody the idea I’d had in mind, I gave up on urban landscapes and returned to the workaday certainties of my fledgling magazine career.

Six months later, September 11th happened. The weekend before the towers fell, my wife found a two-dollar Holga at a garage sale in Silverlake, and brought it home to me. A week after those events, I put a roll of 120 black-and-white film in it and stepped out into my neighborhood, shakily. As most of us had been, I was utterly traumatized by the events of 9/11: horrified down to my bones, alienated unto my soul. I fidgeted and paced for several days, dazed by TV replays of that spectacular carnage. When I couldn’t handle another minute of Wolf Blitzer and Dick Cheney, I headed out to walk and think and mope and maybe to shoot. In that blackened, dizzy mood, I chose the Holga to take along, knowing its reputation for light leaks and errant focus and stupid, wrecked exposures. I wanted to shoot pictures that wouldn’t work out; I wanted to waste my time at something irrelevant and ill-begotten. I doubted any of us would ever be the same again, that order would never be restored, so I spent that day and the next month in the perverse, nihilistic pursuit of negation and self-destruction---walking endlessly, shooting constantly, using my viewfinder to create order and meaning that I knew the Holga couldn’t sustain, that I knew would look pukey and garbled, disordered and meaningless, when finally I encountered my negatives.

Later, I dragged a bulging Trader Joe’s bag to the lab, all my squandered film. And, as before, my contact sheets surprised and baffled me: I was flabbergasted to discover that the work I’d produced with that ratty Holga was actually pretty great---exactly what I’d been hoping for two years earlier, when I’d shot and re-shot my first series of urban landscapes. Somehow, I’d failed to sabotage my best efforts; I’d fucked-up my campaign to create a glorious mountain of crap pictures. How had I accidentally succeeded, when I’d tried so hard not to?

I realized that my earlier assumptions about camera format---that a Hasselblad might succeed where Olympus had failed, and that a 4x5 might solve the problems both suffered---had led me further and further from my nascent “vision”, which actually craved less detail, not more and more and more. By a mile, the Holga delivered that: a general un-sharpness, random areas of un-focus, smudged corners and edges. I remembered that Cartier-Bresson had once called tack-sharp negatives a “bourgeois conceit”, or something like that, but I’d never really questioned the desirability of that fundamental quality; now that I had two hundred rolls to compare to my over-sharp failures, I could see that rich detail might not be everything it was cracked up to be. That’s what’d seemed (to me) so hackneyed and boring and old-fashioned in my earlier efforts with larger and sharper negatives: all that some-old-same-old detail, the grain in the wood and the pebbled texture of bricks and mortar, the stinging delineation of razor-black against holy white, felt like another re-hash of Wright Morris and Ansel Adams in the pages of those classic Aperture magazines. Apparently, I’d been looking for a rejoinder to all that---an anti-Ansel vibe, a dreamier view---but didn’t know it until I quit the search and tried to screw everything up.

Partly, I was trying to make visual my memories of music I heard when I was eight years old, dizzy with scarlet fever and swooning in my bed. My mother played a transistor radio while she cleaned, and I heard those Top 40 tunes only after they’d traversed half the house, down a long hallway, bouncing off walls and oozing past drapery. The detailed dynamics of the recordings were stripped away or rounded off, and what remained for me---what entranced me!---was just the architecture of a song, its broadest strokes, its impregnable essence, and the feelings that bubbled upward through that murk. The plastic camera pictures I began making in 2001 seemed like that, like music from another room. A lo-fidelity version of itself, familiar and deep but different, ravaged by static.

As the pictures of “Sunshine & Noir” began to accumulate in the fall of 2001 and the winter of 2002, the first outlines of a book took shape. But I knew that such ambition would require almost a hundred images---“The Americans” had 83, it’s well known---and that I’d certainly need a year or two to find all those. (It took twelve years, in fact, to achieve that edit.) However naïve my projections were, it was clear that the grief and alienation that had driven the project’s seminal season couldn’t possibly keep its grip on me for so long; I certainly hoped it wouldn’t. I’d begun the project in mourning, and had photographed equivalents of my despair in the neighborhoods of LA, but I knew that couldn’t be sustained---and, anyway, a book-ful of pictures of sorrowful alleys and nihilistic dog poop would make a pretty dreary terrain for viewers to slog across. So, as my spirits rose in the middle of 2002, the photographs began embracing other animating vibes: visual punning, wistfulness, direct wonder, humor, and an elegiac lyricism that was far gentler than the sarcastic, self-deprecating anger I’d started with. By 2013, I’d gathered over a hundred of those images, and thought I might have exhausted my interest in Los Angeles, but the purchase of a couple Mamiya 6s---“real” cameras---rejuvenated me, and I raced back into the field to shoot my color project, “The American Apparel”.

In March of 2002, on the six-month anniversary of 9/11, I’d travelled to New York to photograph the light sculpture that’d been installed in the footprint of the fallen buildings: hundreds of movie priemier spotlights, sending their powerful beams into the heavens. I shot that with my Holgas on a tripod, hours of circling the surrounding blocks while a late-winter snow fell from the night sky. I was giddy with excitement after that, and wondered, Why have I never made pictures in New York? I’d visited three or four times a year since 1997, hustling magazine editors, but somehow hadn’t thought to make pictures on the same streets my best heroes had, Winogrand and Charles Harbutt and Lee Friedlander. I spent the rest of the week doing just that, and then returned in the fall for more, and made two or three trips a year after that, walking and shooting for nine or ten days at a time, in all the buroughs. I continued adding to that body of work for thirteen more years, until 2014, when I began itching for other cities to study. I’d already made portfolios in Paris, Chicago and San Francisco; in 2014 I added Boston and Philadelphia to the “Sunshine & Noir” family, and in subsequent forays I worked in Portland, Seattle, Austin, Detroit and Las Vegas.

MK: What is the work process like for making images for Sunshine & Noir? Are you going out specifically to photograph these images, or are they done while taking part in your day to day life as a working photographer? Do you have a favorite film you use for this? What about color? Holgas are cheap, do you keep more than one on hand at all times?

TA: From the beginning---those brutal weeks after September 11---the pictures that became “Sunshine & Noir” were made by immersion and accumulation, one step at a time through strange neighborhoods, following my nose into whatever sidestreet or vacant lot I fancied in the moment. I studied shopping districts and hillside enclaves from my car as I crossed town on my daily errands, back and forth to the color lab or the rental house, and I made notes about intersections I might return to, at this or that time of day. Returning, I’d park the car and launch out onto the sidewalk, where I stayed for three or four hours, meandering like a drunk through alleys, eyeballing dog poop and Guadelupe shrines and the way shadows played across a garage door. Unbidden, a random, unlikely song would often ooze into my imagination---“Strangers In the Night”, “I Fought the Law”---and as I sang it to myself, over and over and over, it took control of my inner rhythms, my stride, the flow of my thoughts. I must’ve looked like the village idiot. But I knew that those pictures could only be made by that process: space unfolding as one moved through it, juxtapositions looming into harmony and then disappearing as the angle changed, information realigning with every step. One might glimpse the seed of a picture through a driver’s window, but, invariably, that image went to hell when finally confronted, after parking and walking back; the apparent relationship between object and ground, a flag and a porch and a bicycle, had disappeared in the translation from drive-by to sidewalk perspective. So, walking was the only way to truly see what might be photographed---which, in effect, was otherwise non-existent. To do that, one needed a certain intention, a half-day, and a clear conscience.

During those walkabouts, I carry two or three cameras, depending on the time of day. Mostly, I use Kodak 120 film, T-Max 400. Since the Holga’s aperture is set somewhere between f8 and f11, and its paper-clip shutter is stuck at about a sixtieth-of-a-second, the only real way to control the density of the negative is in the lab, not in the field. (That little slider on the top of the lens is a useless contrivance.) So, I shoot one camera on the sunny side of the street---processing the film from that one normally---and another in the open shade on the other side of the street, which rolls I push-process by a stop or so, mostly just to add some “pop” to that murky negative. If I think I might be working in the dusk, or in any kind of deep shade, I carry a third camera with Ilford 3200 in it, processed at 1600 ASA. To anyone familiar with 400 film, these exposure combinations might seem likely to over-do a standard negative, but the sorry fact is, the Holga’s lens---a plastic hunk of junk---is almost two stops less efficient than the everyday, multi-coated consumer lens. It just doesn’t pass enough light. I rate those 400 ASA films at about 160, and pray.

Since the Fall of 2001, when I began “Sunshine & Noir” in the neighborhoods of Los Angeles, I’ve used and retired over 60 Holgas. They simply wear out after a while, usually in the meniscus arrangement of the shutter. Sometimes the lens grows cloudy, or makes vignettes that’re too invasive for my taste. Each Holga is ugly in its own way. I’ve marked each with a letter of the alphabet, so I can label every roll for the lab by the camera it came out of; if those negs reveal an intolerable flaw in the operation of the machine, I know which one to throw away. I’m currently on “MMM”, which denotes a third swing through the code, half way to “AAAA”. My greatest, most treasured Holga was “C”, which had a beautifully-proportioned vignette and a perfect fall-off of focus; incredibly, it lasted twelve full years, and died peacefully in Chicago in 2013.

MK: In an age of digital supremacy in the professional photography realm, why would you step back into film with a project when you really didn’t have to? Is there something about the use of film that simply appeals to you, or are you getting something out of it that you cannot recreate digitally? I suppose the real question is, what’s the psychology behind using film in the modern era?

TA: I must say, I’m not particularly in love with film, as such. I’ve shot it seriously, several days a week, since 1983, and processed negatives and prints in my own darkrooms until about 2007. (I continue to use 120 film in my Holgas, but a lab does the negs and I scan those in my studio.) For over a decade---even at my first “real” job---I filled cassettes from bulk rolls of Tri-X and T-Max, and souped thirty or forty a week; later, I did C-41 on a daily deadline in Noritsu and Fuji machines, and scanned the film into a network. When I travelled for Time and People, we shot transparency film and FedExed it to New York from our location---a nerve-wracking process that tested the wits of all involved. So, for me (and a great many other old dogs), film is quite simply a material onto which our photographic choices and behavior are encoded for transfer into another medium---light-sensitive paper, via the intercession of a darkroom, or an LED monitor, by way of a Nikon scanner. I’m quite aware that, for some very discerning practitioners, the richness of its grain and gradation is a thing of beauty---it’s an object unto itself---and, as a “partner” in the artistic process it forces contemplation and commitment that profligate digital capture just doesn’t. (Also, for those who hope to declare their independence from iPhone culture, a battered old Pentax Spotmatic is a terrific fashion accessory.) My feelings about the uses of film are just more utilitarian, more lived-in, after all this time. However, if the subject is film cameras, I’m all ears.

When I shoot film, my interest is entirely in the cameras and lenses that expose those rolls and sheets. The best of them all, for me, was the first body I ever used: the 35mm SLR, with its perfect rectangular aspect and all those finely-machined works crammed inside, whose watch-like glide and whir I could feel against my palm when I pushed on the advance lever. (After I bought my first Nikon FM-2, I kept it by my side all day and night, ceaselessly ratcheting that little arm while I watched TV and argued with my roommates.) The tradition of dispassionate, anonymous forensic scrutiny that a square frame proposes---it was for years the format used by “artless” workaday pros, the shooters of real estate, PR and crime-scenes---makes the Hasselbald a perfect instrument for this postmodern moment, with its supersharp glass and no-frills, almost military design. I made portraits with a Graflex 4x5 for three or four years, because those classic dimensions fit the human head exactly, and communicate respect for the subject, which is isolated at center stage by the thrillingly narrow depth-of-film that’s intrinsic to that format. And, whichever of those formats I worked with, whatever the mission, I always had a Widelux panoramic camera nearby---the one with the lens that rotated from side to side to make vertiginous shots that curved and undulated.

The Holga is the last of these, and, camera-wise, the least of them. It comprises about fifty cents worth of crap plastic molded into a box whose walls one could almost crush with a bare hand. It’s an “ur-camera”, fundamentally original, with nothing added to the seminal design. How much different is a Holga from a Brownie? But its charm lies there, too. In an environment where even the cheapest little eBay camera kit makes fairly sharp, well-exposed pictures, and where images Photoshopped to pro standards are published wall-to-wall in our newspapers, magazines, and all our various screens, we’re utterly surrounded by well-polished pictures that promote the hegemony of a single standard: perfection. Holgas provide the opportunity to test a modest alternative to that. They make possible a rumble of feedback---the Jimi Hendrix kind---atop the Beach Boys sheen of our everyday visual experience; their negatives give us murky, ambivalent, dreamy options to the insistent, hyper-real onslaught of “useful” images that bombard us all day, every day, in ads for products and promos for TV shows and glowering shots of Trump on our newsfeeds. At some point, of course, the calculations or ingenuity or gut feeling of the photographer has to take charge of those benighted Holga shots---it’s pretty clear when a photographer is leaning on that fucked-up “look” as a substitute for personal vision---but the alternatives the camera provides can open a door, suggest a route, give permission to particular photographers to go ahead and see where “uselessness” leads.

MK: Was there ever a specific job or event that became a turning point of success in your career as a professional photographer?

TA: Early in 1984, while waiting tables in a Mexican restaurant in Lansing, Michigan, I mounted a show of recent street photography at a gallery at MSU, my alma mater. Somehow, Michael Moore---yes, that Michael Moore---saw the show, and asked me to do a couple assignments for the Flint Voice, a rabble-rousing weekly that he was then the editor of. We hit it off, and ended up traveling together that summer to San Francisco for the Democratic National Convention. (That’s where we met the Mother Jones people, who offered him their top job, which precipitated all the weirdness he documented in “Roger and Me”.) Not for the last time, I set aside the personal style that’d served me so well to that point and tried to mimic the look of the newspaper shooters I was rubbing elbows with, but the pictures I made there were so middling and mediocre, I don’t remember a single one of them. (Lesson learned!) I have great memories of that trip, however: I watched David Burnett working with a Mamiya 7 in a dim stairwell, and met Robert Frank on a sidewalk outside the Moscone Center, and found Eugene Richards’ first two books in the bargain bin of a used bookstore next to the Judah train. I thought, So! This is what happens when you get out of Michigan! Even after all the rookie screw-ups I committed on that trip---I crashed a borrowed car, and missed a train and missed a plane and ran out of money and slept overnight at the airport---I still remember thinking that I’d conquered something huge, rounded a crucial corner in life, and that I just wanted more and more of that. So, that was the turning point you asked about: I thought I could do a certain thing, become a particular version of myself, which required proving and testing---and I went off and did that test, at great cost, and learned that I was who I thought I was, and that the sky was the limit. The next step, of course, was to do all that and not make crappy, forgettable pictures.

MK: Do you see a difference between how you approach your personal work versus the images you create for others, or do you feel they inform and inspire one another?

TA: As many before me have said, most artists tell the same two or three “stories” over and over in their work, across a career. Some, like me, vary their techniques dramatically over time, disguising their ongoing intent---I’ve used all the formats and materials, from 4x5” to Widelux to cross-processed color and multiple exposures on customized Hasselblads---but my handful of “stories” remain consistent. The main one is: If we agree that the true subject of a photograph is the photograph itself---that the nominal ‘hero” cohabits the image with every little thing inside the frame, all of which “matters” equally---we become responsible for managing the visual chaos that most everyday scenes are prey to. Our only photographic defense is vantage point and viewfinder, which we deploy to corral and tame all that stuff and crap. Failure is almost a given, but success is the thrill that makes one try again and again. So, my eye surveys every scene for some nexus of line and light and shape, some little dust-storm of visual chaos, that can be confronted and wrestled into shape, for the sake of that thrill. Much of my photojournalism, my portraits and street photographs and urban landscapes, are designed that way, for a surfeit of unruly information, barely controlled by the edges and corners of a two-dimensional frame.

The other “story” I tell and retell is an old one, certainly not of my creation: the single individual inside her environment, happily or not. As before, the many elements of the picture must find harmony with the frame of the photograph, but, in these particular images, those swirling, looming elements clearly aren’t in harmony with the subject. The picture’s “hero”---a striding pedestrian, a dog, a lonely lighthouse---is isolated by design. This being a photograph, that subject is often unaware that she shares the frame with the those graphic elements that define the architecture of the image: a distant bridge, a tree in the foreground, a slashing shadow on the wall. That picture, that arrangement of form and psychology, is Cartier-Bresson’s greatest gift to us, and, along with five generations of photographers, I’ve internalized it into my worldview. Again, those calculations about proportion and balance, the placement of our hero in the frame, runs through much my work, regardless of format, materials, client or end-use.

MK: What is it that inspires you to decide upon a particular project?

TA: Like many photographers, I’m greatly interested in people and their stories, and with social conditions and current affairs---but I don’t initiate my personal projects from those concerns, or from any set of intellectual or spiritual or political ideas. For better or worse, my projects all begin from a consideration of what stuff looks like when it’s photographed, as Garry Winogrand famously said. That urge necessarily drives the ongoing accumulation of…photographs of stuff…which collection is then available for “interrogation”, as they say in grad school. Whenever I’m not working on a specific set of pictures, I range widely in the urban environment, walking in neighborhoods that interest me, and I shoot whatever I see, without prejudice, responding with as much pure visual curiosity as I can muster. After several months of that, certain subjects begin to emerge, certain themes or techniques catch my attention: I might notice, to my surprise, that stray dogs have taken over my contact sheets, or that I’ve collected an abundance of castaway mattresses. Over time I might study my feelings about those subjects, while I pay more attention to them in my walkabouts. A point-of-view might emerge, a swarm of ideas might coalesce around those dogs or mattresses---the vagaries of freedom, the impermanence of love---and I’ll pursue those as I hone my searches and, for the next year, all I’m doing is dogs and mattresses. But, even in that state of heightened attention, other unrelated motifs will always swim into my peripheral vision, and I’ll make a half-hearted snap of such-and-such, and perhaps my next preoccupation will slowly bloom.

MK: During the height of your photojournalism years, was there a favorite camera, lens, and film combination that you felt covered you the best while in assignment? If you were to recreate that workflow today, would you do it the same way, or might you change it up in some way?

TA: By a mile, the aspect-ratio that feels natural and almost perfect to me is 1 x 1.5, which is the standard DSLR dimension, and the 28mm lens is where my eye feels at home. It’s funny and perverse, perhaps, that all my personal projects from 2001 through 2016 were done with square medium format cameras---Holgas, Hasselblads, Mamiya 6s---and lenses that were the equivalent of about 35 and 55mm. But those 15 years of buying and processing 120 film---30 or 40 rolls a week, color and black-and-white---almost bankrupted me, and I reached a point of actual despair about my ability to finish the half-dozen projects I had on tap. (To this day, I still have over 20 pounds of shot, unprocessed film in a refrigerator.) So, when Canon released its 53-megapixel EOS 5DSr in 2015, I took notice; with a sensor that big, I could continue shooting and printing the huge squares that, for all my current and potential gallerists, was the new normal. But, holding that perfect 35mm body in hand was too much like my innocent days of yore, and, as soon as I could, I stopped using it to make squares and returned to that essential full-frame, shooting wide. All three of my current projects make the most of that classic horizontal, which I’m delighted and relieved to be producing at no extra cost except for hard drives by the case full.

MK: Anyone working in an artistic field has matured and grown over time. Is there anything you’ve discovered lately that you’d like people to know about you or your creative process?

TA: For most of my career, the photojournalism I practiced in my professional capacity was complemented by personal work I did on nights and weekends. In effect, I was doing two jobs side by side---which might account for the chronic feelings of frantic-ness and exhaustion I’ve had since I was twenty-five. The gallery projects I did up until 2000 had shared with my best newspaper work a common subject: people in public, performing ritual behaviors in ritual wardrobe, negotiating the narrative and the space itself with one another, moment by moment. As a staff photojournalist, I bore responsibilities to my readership for accuracy and straight-shooting, so my “take” on those events resembled the “real world” in which they transpired. But my personal work, which drank from the very same pond, tried to propose an “un-real world” that was off-kilter a bit, a non sequitur. By 2001, however, I’d grown tired of those crowds and scenes, and pushed my nascent magazine career in the direction of lit location portraits, whose method was a drastic change for me: I was no longer chasing people through a fluid situation, but rather was taking complete control of a “set” I’d chosen, which was usually peopled only by me and an assistant and our subject, maybe a publicist. Likewise, the milieu of my personal work shifted away from crowded rooms, and became the empty streets I trolled for my urban landscapes, Holga in hand.

A common feature of both endeavors, as I moved further from the aesthetic of daily photojournalism, was my growing desire to control the look and feel and vibe of the picture---to “create a world” that had its own gravity, a color palette of my choosing, a quality of light that diverged from the everyday. (So, a through-line from “Social Studies” to “Sunshine and Noir”, with a year off in between.) In the magazine work I was certainly the author of the light we employed, down to the last detail, but the Holga work allowed a deeper immersion, because I chose the subjects myself---which blighted alleyway, which neon marquee---and could craft the presentation so that each picture spoke to its neighbors and the others nearby in a grammar I created as I went, honed as the volume of images grew.

Looking back on that work, and the projects that followed, I see that my process has continued maturing along those lines: my best hope is to use the everyday stuff that’s generously provided, in bulk, by the workaday world, and to transform a subset of all that---a particular city, a certain aspect of the built environment---into a world of its own. As I’ve grown, and gained understanding of that urge, I’ve become more committed to the very disciplined method required for such “world-building”. The work I value the most, whether my own or by others, are the projects that slice into “reality” at a particular angle---a “way of seeing” a particular subject---while deploying a particular and limited arsenal of tools in a consistent and coherent way, over the course of twenty or thirty pictures. By those means, one excludes everything that doesn’t add to their exposition of that “world” and how it works. And one pays the strictest attention to light and it’s qualities---always, always, photographs are about the vagaries of light as it strikes the surfaces of the visible world. Examples? Using a strict technique, Todd Hido created a world with his pictures of suburban houses at night, as did Alec Soth in “Songbook”, with his choice of subjects and the benign, “pedestrian” strobe he exposed them with. Jacob Au Sobel follows in the tradition of Anders Petersen, Ken Schless and Daido Moriyama in creating high-contrast, flash-blasted fantasias that reveal the mortification of all---the flesh, the spirit, the ragged city---in jarring prints that thrive on deep, inky blacks. Once they’ve demonstrated “the rules” of the world they’ve set up---the camera system and the film, the use of light, their compositional strategies, the use of saturation and contrast in their printing---those photographers never veer from that aesthetic, out of necessary respect for the fragile “gravity” of the world they propose to show. Humbly, I attempt that same discipline and philosophy, however much I might fall short of the mark.

MK: I appreciate your willingness in answering these questions, Tom. Normally, I’d say that since we share the same city, let’s go out for a beer and you can fill me in about the latest news. But why not share that here as well? Do you have anything new in the works that you’d like us to keep an eye out for? What’s next for you?

TA: Michael, I reached a genuine crisis in my shooting career, back in the middle of 2015. I’d just finished “The American Apparel”, my color series about fashion advertising in the working class neighborhoods of LA, and was testing out three new ideas I’d been itching to get to---all using the same materials as “TAA” had, 120 film in Mamiyas and Hasselblads. But the prices of film and processing had been rising fast since about 2012---Kodak, always myopic and arrogant, chose to penalize their dwindling adherents with higher prices, rather than embracing and supporting us---and I was reaching a breaking point. I was spending seven or eight hundred dollars a month on 120 Portra, and well over a thousand processing those rolls. As the fieldwork on my new projects became more intense, and I required more and more film, I decided to spent my funds in that pursuit and stopped processing altogether, refrigerating a growing pile of exposed rolls. (At one point those bins and bags of film weighed in at 32 pounds.) Clearly, that practice was unsustainable, and the future of my whole endeavor was at risk. When I could no longer deny the reality of that situation, it broke my heart.

Naturally, digital capture had occurred to me. I’d been using Canon’s 5D line for ten years in my professional work. But, as you know, the advent of high-performance archival printers, back in the early 2000s, had made possible the creation of larger and larger prints, which had become the norm in galleries and museums---and my own gallerists frequently asked for big-ass pieces that I didn’t believe could be made from those 22-megapixel bodies. Of course, Hassleblad and some others made medium format digital cameras that could certainly satisfy that need, but their price tags were out of sight. I thought, if Canon could ever market a DSLR that doubled the size of that Mark 3 sensor, I might be persuaded to surrender my beloved Mamiyas and Hassies, kicking and screaming. Then, out of nowhere, they did just that, introducing the 50-megapixel EOS 5DSr that very summer. I sold a couple prints after Thanksgiving, and two more just before Christmas, and by New Year’s 2016 I had that camera (and a supersharp 24-70mm 2.8 lens) hotly in hand. I dialed a square field into the viewfinder and leapt back into the breach, thrilled to be able to work all day without tithing a penny to Kodak. I edited my work the same evening, while film I’d shot a year earlier was still unseen, moldering in the refrigerator in my studio. A new lease on my miserable career!

After a while I reformatted the files, and started shooting that camera in its full-frame aspect, 1 x 1.5. When it comes to camera bodies, the feel of them in hand and the shape of the “negative” is, to me, all of a piece, and that body was inescapably a 35mm machine. I’d grown up with those dimensions, and still believe them to be almost perfect. Freed from the square, I decided to change the look of my work even further, and began shooting my urban landscapes with a brilliant strobe, powered by a Dynalite 1000ws pack I wheel around behind me in a carry-on bag, or hoist up onto my back. A couple of those projects, begun almost three years ago, are almost finished, and three more are gaining momentum.

I’ve sent along a handful of frames from one of those projects, “The Nature of The Beast”. Those of us who live in Los Angeles are familiar with the variety of desert plants and flowers that sprout everywhere around us: wildflowers, bougainvillea, agave, cactus. Their story, I’ve realized, is one of accommodation and insurgence: however much cement we pour onto the hills and canyons of this basin, the desert abides. In the strangest of places, its persistent vegetation pokes up through the cracks and seams in the built environment, unbidden, climbing fences and telephone poles and sprawling randomly across alleys and sidewalks everywhere. This portfolio tilts toward bougainvillea---which, quite simply, pops like crazy in the strobe light---and includes other bright and gnarly blooms in neighborhoods from San Pedro to Echo Park to Venice and the Hollywood Hills. Currently, there are thirty pictures in the portfolio, which I’ll finish it for good in March or April, after I get one more winter’s work under my belt.

Meanwhile, I continue to shoot in American cities with my Holgas---Nashville and Memphis are next in the New Year---but I wouldn’t recommend anyone “keep an eye out for” those images, which always take a year or so to see the light of day. A trip like that, which normally lasts about three weeks, generates at least 200 exposed rolls of T-Max and Ilford 3200. Whatever else one says about film, the “professional” or serious use of it is very labor intensive and time-consuming for someone working alone, like me; the quickest I’ve ever turned-around a finished, 25-picture portfolio from one of my city safaris was two months, which was a pretty dizzying pace.

Connect with Thomas Alleman:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Kirchoff is a photographic artist, independent curator and juror, and advocate for the photographic arts. He has been a juror for Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and has reviewed portfolios for the Los Angeles Center of Photography’s Exposure Reviews and CENTER’s Review Santa Fe. Michael has been a contributing writer for Lenscratch, Light Leaked, and Don’t Take Pictures magazine. In addition, he spent ten years (2006-2016) on the Board of the American Photographic Artists in Los Angeles (APA/LA), producing artist lectures, as well as business and inspirational events for the community. Currently, he is also Editor-in-Chief at Analog Forever magazine, and is the Founding Editor for the online photographer interview website, Catalyst: Interviews. Previously, Michael spent over four years as Editor at BLUR magazine. Connect with Michael on his Website and Instagram!